Engaging children in the complex relationship between humans and the rest of nature (take 1)

Establishing an ethical relationship between people and nature is far from straightforward. In this essay I consider how we might engage the young children at Newtowne School in consideration of this complex relationship.

Establishing an ethical relationship between people and nature is far from straightforward. In this essay I consider how we might engage the young children at Newtowne School in consideration of this complex relationship.

“I could have them still here and I also kinda want them away”

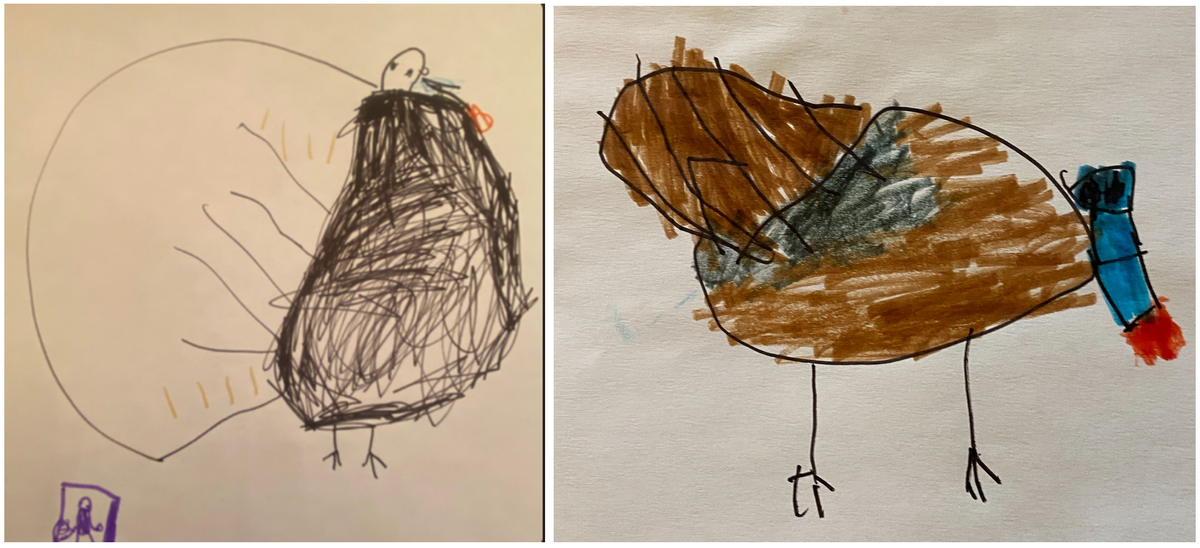

In a conversation between five-year-olds Avery, Hugo, and Farryn about the wild turkeys that live in Cambridge, there are different opinions and expressions of uncertainty. Avery thinks the birds, who have a reputation of harassing people, should be removed from the city. Farryn is not sure, explaining, “I don’t want them to move away, but they could go in a cage in a zoo so they don't bother anybody.” Hugo is also of two minds: “I could have them still here and I also kinda want them away.”

The question of the wild turkeys is just one of the numerous relationships between people and the rest of nature to be sorted by the citizens of Cambridge. In the never ending battle to control rats, do we use poison which is effective against them yet harms birds of prey? During West Nile virus outbreaks (spread by mosquitoes), is spraying pesticides–which will kill other insects–the way to go? The list of issues goes on and on.

In this essay I consider how we might engage the young children at Newtowne School in consideration of the complex relationship between humans and the rest of nature. I explain the importance of engaging young children in complex topics, share a transcript of conversations about wild turkeys as an example of children engaging in such questions, and wonder how to expand on such conversations. This essay is a first take on this question. I hope it will promote conversations that will improve my community’s practice in this area--and perhaps inspire others to dialogue as well.

The importance of engaging children in complex topics

A central goal of my work at Newtowne is building children’s solidarity with nature; growing a feeling of kinship, belonging, and empathy with the more than human world. Creating such a relationship is not straightforward.

Consider the Spotted Lanternfly.

With its red, black, brown, and blue color scheme, I find it an attractive insect. I think many children at Newtowne would agree. And for the past several summers there have been campaigns in New York City and other locations in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast of the U.S. encouraging people to kill them.

There are considered reasons for these efforts. Introduced from Asia, Lanternflies lack natural predators in the U.S. and have spread across the eastern seaboard. They damage vineyards and other crops, and produce a sticky honeydew that many people find offensive.

As an educator working to help children feel kinship with the flora and fauna that we share our city with, I’m ambivalent about these campaigns. I recognize the need to curb the spread of the Lanternfly. At the same time, our ecosystem is complex, made up of many different parts that interact in multiple ways. I have seen preschoolers randomly stomp on spiders, ants, and other small critters, an impulse I try to curb. I question the simplistic message–stomp–and wonder if it misses an opportunity for deeper education. Without a thoughtful conversation about why it is good to kill Lanternflies and not spiders, I worry that my efforts to dissuade children from randomly killing will be compromised.

A general principle: question simple solutions to complex issues. Raising children who are prepared for the challenges of the world’s entangled environmental and social issues involves helping them become practiced in grappling with complex issues. As Matt Karlsen from the Center for Playful Inquiry (https://www.centerforplayfulinquiry.com/) explains:

Living in the anthropocene [the current era of human driven climate change] involves living in a world where best paths forward are often not clear, so we each need to decide what values we want to guide us. Coming into contact with others's stories [and opinions]…is a source of tension which leads to creativity and learning. We need to help children stay engaged, to listen, and to play to create new possibilities –and one way to help them do that is to avoid the norming of a singular attitude.

In adulthood our children will face numerous situations where answers aren’t clear, where there will be important trade-offs to weigh, and different perspectives to understand. They will need to know how to navigate complex topics with others.

Luckily, young children don’t read Piaget

But can young children engage in complex topics? During my graduate school education in the mid-eighties, the ideas of Jean Piaget dominated courses on intellectual and cognitive development. While there is much wisdom in Piaget’s work–it helped fuel the cognitive revolution–one interpretation of his theories is that young children are binary thinkers; that they see situations as right or wrong/good or bad. As a result, they are incapable of dealing with ambiguity and complex topics. This idea has a deep hold. Years later a reviewer of an article I wrote with colleagues describing my kindergarteners’ inquiry into democracy urged for the piece's rejection because, “Young children are incapable of understanding such a complex topic.”

The good news is that young children haven’t read Piaget, so they don’t know what they aren’t supposed to be able to do. My experiences with young children have taught me that they can engage in conversations about complex issues, sharing opinions, listening to others’ perspectives, and even changing their minds. For example, one year I facilitated a group inquiry into spiritual beliefs where the children asked questions such as: is there a God; what happens when people die; and who were the first people? The children carefully considered the ideas of adults they called “god experts'': a priest, a rabbi, an imam, and an atheist philosopher. They shared their beliefs and listened to the beliefs of their classmates, beliefs that ranged from literal interpretations of the bible to outspoken atheism. That there wasn’t one right answer or correct point of view was a source of pleasure. As six-year-old Max explained at the end of the inquiry, “The fun thing about different beliefs is that they are different.”

This isn’t to say all subject matter is fair game in preschool, or that four-year-olds need to know the full extent of humanity's problems. Each community must decide what issues to bring forward to children (though it is impossible to have complete control over what kids will hear about). My point is that young children can engage in complex topics and it is important that they do.

The Everything Questions Podcast, Episode 5

“Do you have questions? Cause we have answers. Join us together for our class podcast.” So starts every episode of the Everything Questions podcast. Created by Green Dragonfly classroom teachers Maggie Oliver and Vaidehi Desai, each episode is devoted to their five-year-old children answering questions submitted by members of the Newtowne community and other friends on a specific topic. Topics have included dinosaurs, spiders, and writing books.

Knowing of my plans to help the Dragonflies create an episode on the school Critter Count, a census-like activity aimed at increasing awareness of the animals we live amongst, our director Caitlin Malloy encouraged me to ask the children questions where there could be disagreement and debate. In other words, questions about complex topics. I decided to ask the children about the wild turkeys of Cambridge.

Cambridge, Massachusetts (USA), where Newtowne School is located, is a densely populated urban area and home to a robust flock of wild turkeys. Though native to the area, wild turkeys had been completely eradicated in Massachusetts by the end of the 19th century. In the 1970s a flock of 40 from New York were reintroduced to the state and have thrived, now with a population of over 20,000. In Cambridge, our turkeys favor the expansive yards on Brattle Street and the wide grassy areas of Harvard campus, but will make appearances on Mass Ave and other busy thoroughfares.

My fellow Cambridgians have diverse and often strong opinions about the turkeys. There is a Facebook page dedicated to turkey enthusiasts who share photos of the birds in various settings. On the other hand, others describe them as “feathered fiends” and “rogue birds.” Their occasional aggressiveness and a lack of regard for traffic patterns (crossing streets and snarling traffic), provoke hostility towards the turkeys.

The kids at Newtowne are well aware of the wild turkeys. Most have seen these impressively large birds and likely have heard adults sharing opinions and stories about them.

Given the different opinions, the turkeys seemed to be a perfect topic to engage children in the complexities of city dwellers' relationship with the rest of nature.

“Should we move the wild turkeys out of Cambridge?

What follows are transcripts of three groups of Green Dragonflies discussing wild turkeys. You can listen to the conversations on Spotify where the Everything Question podcast can be found (check out episode 5 starting at eight minutes in). To provide a sense of how ideas emerge from children’s back and forth, I’ve included the entire conversations.

I introduced the issue of turkeys as a question coming from a colleague named Emma, who when visiting from China became curious about the birds. I explained that Emma had, “heard stories about the wild turkeys being mean to people like the UPS guy or sometimes they stand in the middle of the road and block traffic so cars can't go by. Or sometimes they get on the tops of cars and they scratch the paint. So some people say that we should move the wild turkeys out of Cambridge somewhere else?” Then, to provoke conversation and debate, I asked the children, “Do you think that is a good idea to move them away? Or do you think they should be allowed to stay in their house?” Here are the children’s responses:

Group 1 (Avery, Farryn and Hugo)

Avery: I think we should move them.

Ben: Avery, why do you think that?

Avery: So they don't do that any more.

Farryn: Well, I don't think we should move them. Cause I like turkeys. Cause they're funny. But I want them to move, but I just don't want them to move at the same time…

Hugo: Also at a place. There was some turkeys still in the cage and some were just wandering out of the cage. But it was like a fun place…

Ben: Avery would like them to be moved. Farryn is like, part of her wants them to be moved and part of her wants them to stay. What do you think?

Hugo: I like when they go gobble gobble.

Farryn: Yeah, because that's a funny noise. That’s what I like about them.

Hugo: I kinda like how their little thing goes the drip, drip, drip.

Ben: You mean the thing on their neck?

Hugo: Yeah. Drip, drip, drip.

Ben: Avery, hearing this, does this change your opinion? Do you still think they should be moved?

Avery: I still think they should be moved.

Ben: So you're solid about your opinion.

Hugo: I could have them still here and I also kinda want them away.

Farryn: I have something else. I don't want them to move away, but they could go in a cage in a zoo so they don't bother anybody.

Hugo: But I think some of the ones that were just wandering around, they probably jumped over a fence or squeezed themselves through this fence and got out. To get out of their cage.

Farryn: But what if you put a glass cage, or maybe a plastic cage with really hard, hard, hard, hard, hard plastic? Or metal ones.

Avery: They would probably break through it if it was glass and then get hurt.

Farryn: Yeah. Otherwise you could do a metal one.

Avery: Yeah. Or you could do a metal one.

Hugo: But they would get some scrapes probably. Maybe little scrapes.

Avery: What if it was made out of wood? Then…

Hugo: That might hurt their beaks because it might crush their beaks down.

Avery: If it was wood it would be hard for them to get out.

Hugo: But if they tried really hard it might accidentally break their beak into pieces.

Avery: What if you did wood with holes in it that were the right size for its beak to get out?

Farryn: Or you can make a little door for it to get out.

Avery: But then it would be hard to get it back in.

Farryn: Oh…but if it had a rope attached to the turkey it could get out and then the human could attach the turkey to it and it could just stay on the rope. And the human could unattach it and get it back into the door and lock it.

Ben: Do you guys think that is a good idea?

Avery: But then it would be hard for the turkey to get out the door. Unless there was just a big hole and a cover for it that fit in the hole.

I am delighted by the children’s commitment to finding a solution that helps people and doesn’t hurt the turkeys. Even Avery, who is clear the turkeys should be moved, offers ideas to protect the birds. And I wonder about providing children more information about the complexity of this situation. Specifically, Hugo seems to think the wild turkeys he encounters in Cambridge are escapees from captivity, having jumped over or squeezed through enclosures. Would his (and others’) opinions be different if they knew that turkeys are indigenous to Cambridge?

Group 2 (Adien, Mateo, and Sofia)

[After summarizing Group 1’s conversation]

Ben: What do you think about moving the wild turkeys? Do you think that would be fair to the turkeys to move them away from their homes?

Mateo, Sofia & Aiden: No!!

Ben: Why?

Mateo: Because they won't have their food anymore and they'd have to collect a lot of food again.

Sofia: And they have to drink some water also.

Mateo: And they would have to build a house.

Ben: But what about the people who are scared of the wild turkeys? How should we help them?

Mateo: To be alone. They have to be alone.

Ben: Away from the turkeys?

Mateo: Yes. No. Maybe the wild turkeys can just be in the forest.

Adien: Or maybe they could just be in the zoo.

The children’s immediate and full-throated support of the turkeys is noteworthy. But they don’t see the situation as black or white, and offer thoughts to help people when that side of the story is shared.

Group 3 (Afomia, Alex, Henry, and Rushaan)

[After reviewing the previous conversations]

Ben: Do you think that the Wild Turkeys should be allowed to stay in Cambridge? Do you think they should be moved?

Alex: Allowed to stay in Cambridge.

Rushaan: Allowed to stay in Cambridge.

Henry: Stay in Cambridge.

Ben: Afomia: Do you agree?

Afomia: Yeah.

Ben: Why do you think that?

Rushaan: Because then they will lose their homes here.

Alex: Yeah.

Ben: And you want them to keep their homes?

Rushaan: And then they would not be where they were before. And then they will not go back. And they will miss their house.

Ben: What about the people who are afraid of the wild turkeys or the wild turkeys bother them. What should we do to help them? Do you have any suggestions?

Henry: Build a house [for the wild turkeys] with a hundred pictures of wild turkeys.

Alex: I think the wild turkeys like to eat Slingy Dags [the Green Dragonflies’ name for gnats]. They think they'll be tasty.

Ben: So if there's too many Slingy Dags, the wild turkeys would take care of that problem?

Alex: Yeah…I think they like them and I think they might have them for dinner, breakfast, or lunch.

Rushaan: And maybe if you made a house that has things Slinky Dags would eat..that are for the wild turkeys. They could eat the Slingy Dags. So then they won't bother the humans.

I am struck by the children’s awareness that the turkeys are part of an ecosystem (that they eat insects that may be a nuisance to humans). Though their support for the turkeys is based on more than self-interest, and seems motivated by genuine care for the birds.

Continuing such conversations: cats and birds

I am impressed by the Green Dragonflies ability to listen to others and explain their ideas in clear and friendly ways; to engage in substantive conversations about a complex question with no one answer. They clearly enjoy thinking together. Their commitment to solving problems (e.g., what would be a safe way to contain the turkeys) is lovely.

It is important to note that the Dragonflies' ability to converse was nurtured over time. Some of them had been practicing listening and sharing different points of view since they were Orange Sea Stars, the toddler classroom at Newtowne School. This ability to engage in complex topics is a schoolwide, multi-year project.

Going forward, I wonder about finding other topics children can discuss and authentically contribute to. A possible topic: cats and birds. The Boston Birding Festival (https://www.bostonbirdingfestival.org/posts/lets-talk-about-cats/) is hoping to start a dialogue about the impact of outdoor cats on the bird population. I think this is a conversation that the Newtowne children could provide an interesting perspective.

With the upcoming presidential elections in November, the start of the next school year bumps up against what is sure to be a fraught time in U.S. politics. Whether you are reading this essay before or after this event, it is clear that many adult Americans (certainly those involved in politics) seem stuck in binary ways of thinking where people and ideas are either good or bad/right or wrong, and lack the ability to engage in complex conversations.

Coda: What about trees in a city?

Near the end of the third group's conversation about the wild turkeys a different and completely unexpected issue arose when Rushaan began talking about some trees that he had seen cut down. He was clear that felling the trees was wrong. Alex disagreed, arguing that, “If a tree gets too big or too old it could fall over and it could hurt a person. Or a person driving a car. It could bonk their head or hit a wire and start a fire.” Rushaan immediately countered, “Those trees near Central Square that were cut down were not too big and not too old. But those silly people cut them down. Those trees were not going to hurt people.” Voices were raised. Tears of frustration were shed.

So what about trees in a city? Are they a critical part of the ecosystem–a habitat for animals, a source of oxygen, a way to sequester carbon, and a source of shade and cooling? Are they a potential hazard that can harm people and property, disrupt the provision of electricity, and impede needed development? We had stumbled upon another complex issue.

In the middle of it all, a colleague that I hadn't seen in many years walked through the studio on her way to our director Caitlin's office. While she is a seasoned early childhood educator who understood that the tears are part of teaching young children, it was not the scene that I would have hoped she would have encountered.

Indeed, as a child of divorced parents, I am uncomfortable with such overt conflict and have the impulse to try to smooth things over when disagreements arise. At the same time I realized that I need to embrace these moments as learning opportunities. When complex issues arise I need to help children navigate them.

So after acknowledging Rushaan and Alex’s big feelings, I noted that how we take care of trees in our city is a complex issue and that people will disagree about the right thing to do. I said that I was impressed by how clearly the two were explaining their ideas and by how much they cared about the issue. I then ask the children to restate opinions. While they continued to disagree, Rushaan and Alex carried on the conversation, listening to each other and expressing their ideas in more measured tones.

Cultivating children’s understanding and appreciation that there is often more than one way–more than one explanation or practice or solution or perspective–involves complex teaching. And it is necessary. When it comes to forming ethical relationships between people and the rest of the world, there is a lot to talk about. We all need practice in having these conversations. If we are open to it, working with young children will provide lots of practice.