From Abundance to Enough

Talking About Drought With a Five-Year-Old

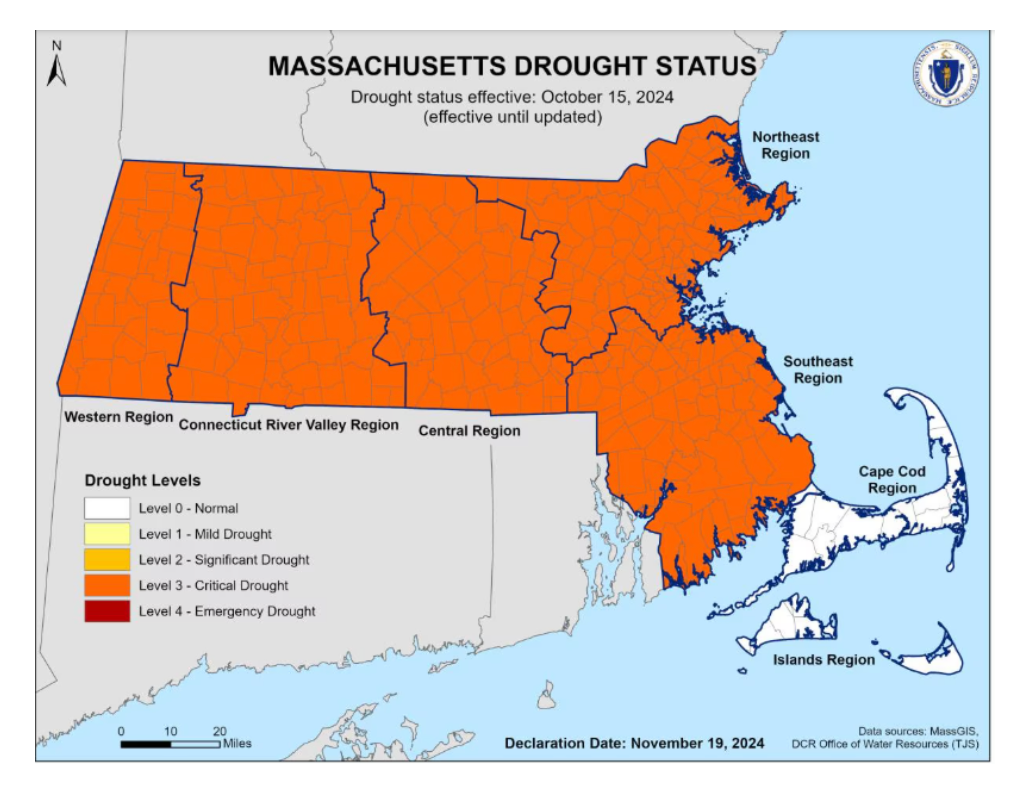

My son Velcroed his Stride Rite sneaker — is this the right foot? and scrambled out the door into autumn. What’s that smell? Smoke. Ashes. That Monday morning before Halloween, our city street smelled like smoked ribs. Brush fires, we learned, had broken out about 20 miles north. A weather phenomenon called a surface inversion had trapped smoke close to the ground through our region. We don’t live in the arid Rockies or dry valleys of California, but in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Drought is rare in New England, but there we were.

It hadn’t really registered for me that my rain boots had sat idle in the closet since spring, if I’m honest. Months of clear summer days led into crisp fall ones, leaving Eastern Massachusetts in severe drought by November. A week after the brush fire, I learned Cambridge had introduced water restrictions, including a plea to residents to take shorter showers and run loads of wash only when full. That same evening, I paused on the stairs as my son, then five-and-a-half, skipped steps ahead of me. Bath or shower tonight, I asked him? Would I mention the water restrictions?

My son is growing up in a well-resourced home in a well-resourced community. This means that scarcity, war, climate catastrophe remain abstractions, for the most part. My spouse and I get to make conscious choices about how much of the world’s suffering and problems to bring into view. It’s a very fortunate situation to be in – fortunate, complex, and increasingly fragile.

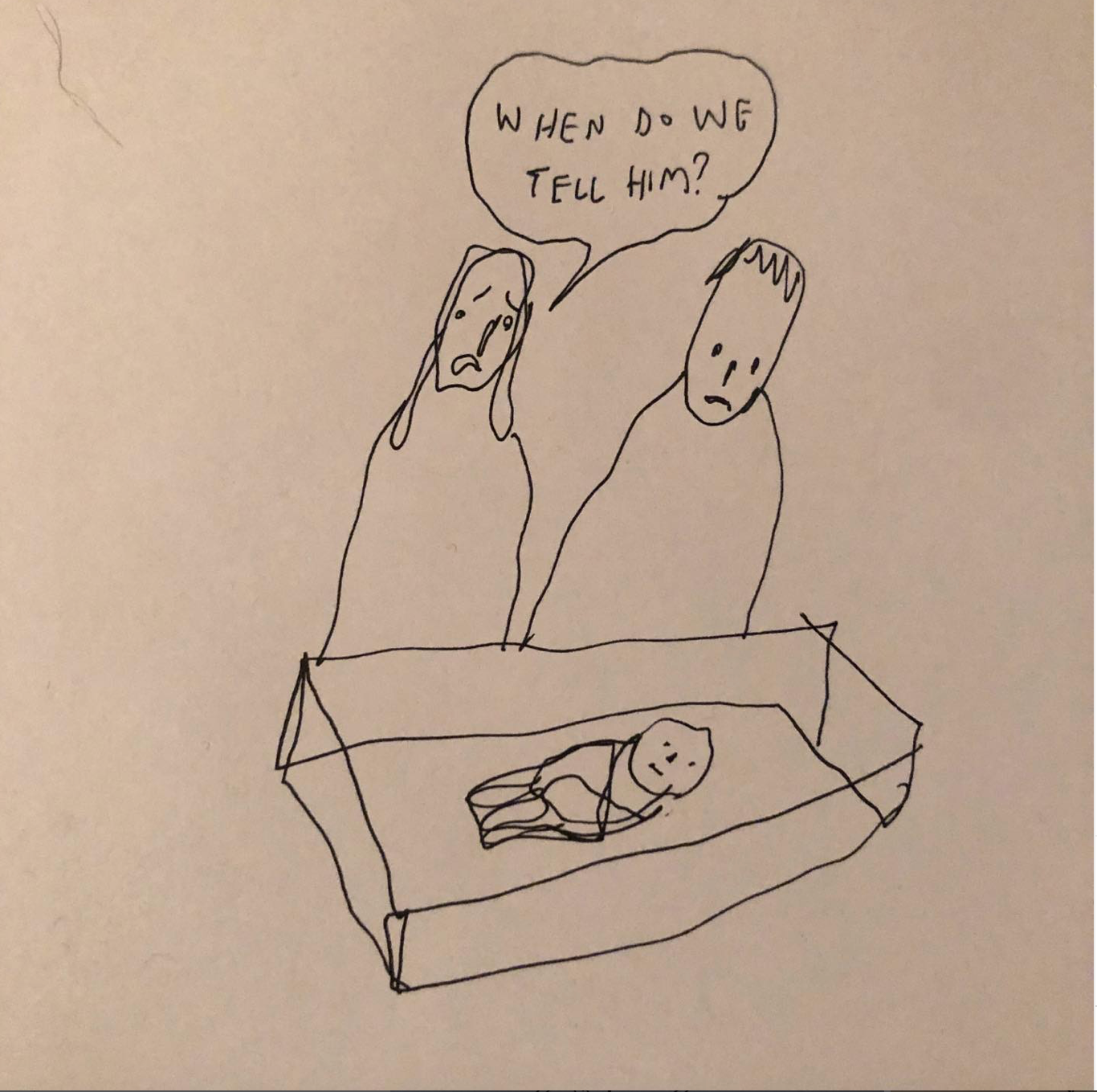

Our son experiences what we call child-size disappointments: a birthday party missed because of a stomach bug, a family trip curtailed by a winter storm. He babbled and giggled through Covid-lockdown as a baby in 2020 — life has had few disruptions. I’ve seen my family’s position summed up well in a cartoon by New Yorker contributor Liana Finck: “When Do We Tell Him?”

In the affluent communities where I have taught pre-kindergarten and kindergarten, and where I am raising my son, the socially-conscious teacher and parent sees it as their duty to teach children about injustice and environmental degradation, the sooner the better. There was a time I preached this gospel, but for years now, it has sat uncomfortably for me, for reasons rooted in my own childhood experience and my years teaching. In this post, I recount the struggle to teach about climate change and also honor childhood, using the notions of abundance and enough as guides.

Plant a Tree, Turn Off a Light: The Individual Responsibility Approach

A millennial, I came of age watching Free Willy, aware that deforestation was bad and planting trees was good. I was raised on the ethic of individual responsibility. I remember our local power company coming into school to teach us to turn off the lights when we left a room — a coloring page with a light bulb to help drive home the point. (I've since learned they dragged their feet in transitioning to cleaner generators through the 1990's.) The apple seeds I pressed into the dirt of our suburban backyard never sprouted. I kept growing out of clothes, producing more waste. Some nerve I had. For a variety of reasons — personal psychology, gender, family culture— I felt my very existence was a problem, a drain.

In more than a decade as a teacher of young children, I encountered more than one child who had absorbed some of these same well-intentioned messages from their grownups about consumption, and applied them in ways surely never intended. I recall a child who quaked at the prospect of washing his hands before lunchtime because he didn’t want to waste water. In a memorable moment a few years ago, I taught a student, herself named for a biome, who could be a slow and distracted eater. Her parents were dismayed by the nearly full lunchbox she toted home some days.

“[Biome],” I reminded her one day, “remember to take some bites of your chickpeas. Your body needs energy for the afternoon ahead.”

“Amy,” she snapped back. “Energy is BAD for the environment.”

My attempts to clarify went nowhere. A solar-powered car on a cloudy night.

For every student who stressed about consumption in these ways, there were two dozen who needed reminders to take only two paper towels, not seven, to dry their hands. Still, flashes of austerity nagged at me, both because of my own personal history and because it was pretty easy to teach children to “take two!” and much harder to convince a brow-beaten child terrified of wasting water to wash his hands at all.

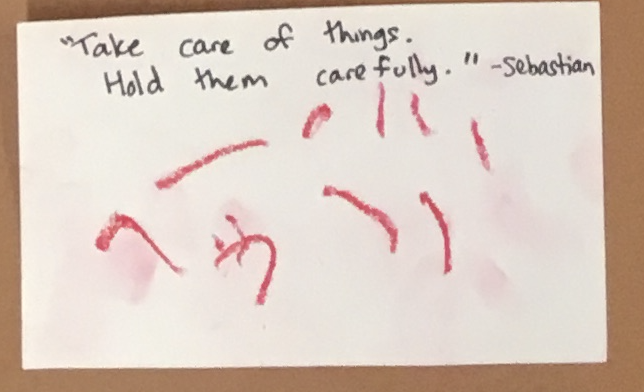

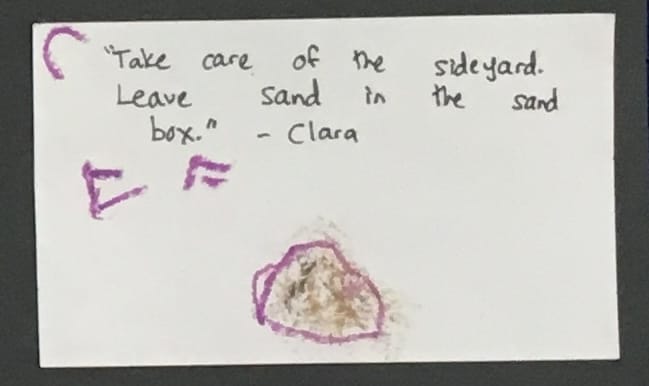

So, I taught students each year about taking care of the environment in small ways: to take care of our classroom, Aria, 4, exhorted: “put your lunchbox under your chair.” Lilly, 6, urged, “take care of the trees. Leave the leaves on the trees.” I aimed for a light-touch approach.

Early Childhood North Classroom Agreement (2018-19)

The Abundance Mindset

Based on these experiences, I’ve wanted to raise my son with an “abundance” mindset —a buzzword with slippery meaning, to be sure. I take it to mean that there is enough to go around. Advocates for an abundance mindset encourage gratitude and enjoyment of what we have, in contrast to a scarcity mindset, which emphasizes competition and stress. I still remember my high school American History teacher, aptly named Mr. Woods, returning a handwritten assignment to me, my paragraphs pressed in narrow-ruled loose leaf that bulged with grooves of blue ink on front and back.

“Amy,” he told me, “this is your education. You are learning to think. I want you to write double spaced, single-sided. I want you to use as much paper as you need.”

Yes, This WAS my education. I try to think about the big picture: farm subsidies, agriculture, waste. Maybe Mr. Woods was right. Maybe I didn’t have to sweat the looseleaf. I had plenty of looseleaf paper, why not use it for learning?

As Americans who drive many places, heat a home in winter, fly on airplanes to visit family and friends, my family’s carbon footprint is massive. We all find ways to live with the cognitive dissonance of our impact — I remind myself we live in a townhouse rather than a sprawling single family home, that we are vegetarian, and that we have one, not multiple children. I try to feel okay about where we have landed by choice and circumstance. When my son doesn’t finish his black beans I don’t sweat it and I don’t want him to sweat it. I put them into Cambridge’s curbside composting and move on with my day. Others, for financial, cultural, and yes, environmental reasons, have a very different approach, teaching children about food waste early on.

So far, it's been a tremendous joy to see my son’s positive self-image, his confidence that he is worthy of our time, attention, love, and resources. Yes, we are also raising him to consider others: on a good day, he can carry a tray of cookies around a room, offering one to each guest, and only then take one for himself, last. On a good day, he can take responsibility for a spill and grab a towel to clean it up. We emphasize these acts in the interest of character, more than ecological concerns. That doesn’t mean I want to protect him, forever, from the realities of scarcity, privation, ecological crisis.

The Enough Project

Recently on this newsletter, Ben Mardell introduced the “Enough Project.” In his work at Newtowne School, he strives to cultivate:

“an awareness that there are limits to what human beings can take from the earth without profoundly harmful consequences. It involves socializing children towards considered and ethical consumption preferences.”

I was particularly drawn to Mardell's caution about how to go about teaching enough:

“Rather than involving rewards and punishments or shame and guilt, it involves directing children's attention to what gives life meaning.”

I’ve found this framework useful for introducing issues of climate change with my son—as he leaves the preschool years, I’m ready to move from abundance to introduce the complexity of enough.

Talking About Water Restrictions

All of these thoughts flooded my brain as we made our way upstairs to start bedtime routines that Sunday in November, water restrictions newly in place.

The context for this conversation is that my son had recently begun to prefer quick showers to baths, making a shower a pretty easy sell.

“Tonight I’m going to ask you if you want to take a bath or a shower. I wanted to tell you, actually, that we have a chance to do a small helping job for our community with this choice.” I had his attention.

“Do you notice that it hasn’t rained much lately? Today I learned from Jessica that Cambridge has water restrictions. That means the water in Fresh Pond is lower than usual and the city is asking everyone to use a little less water so that there’s enough for everyone. This means taking a shower instead of a bath.”

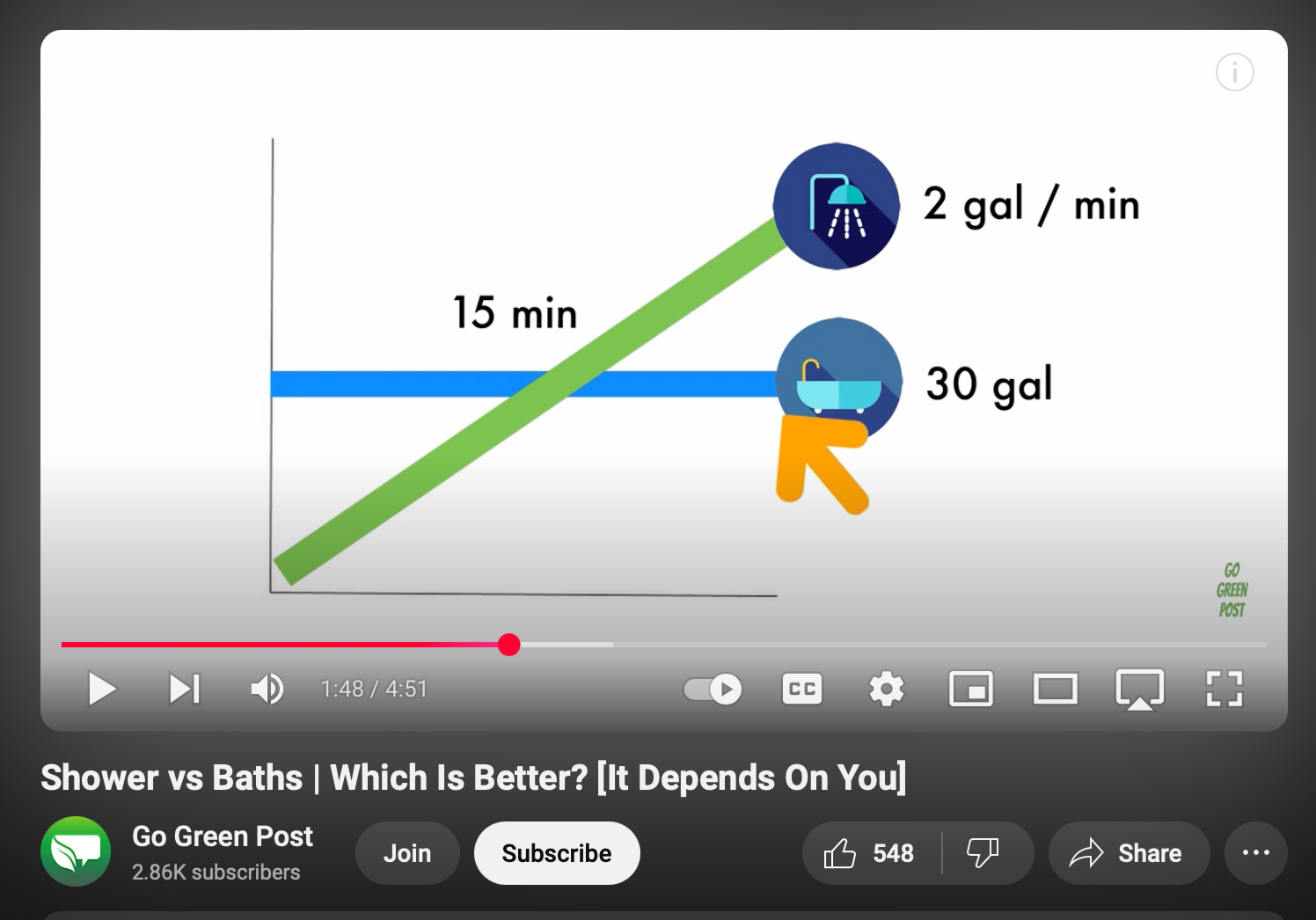

Children have a way of taking a conversation in a direction we least expect — this case was no different. “How do we know which?” my son asked. “Like how do we know which is less?"

A creature of his environment in STEM-fueled Cambridge, my kid wanted the data. I pulled out my phone and found a short video that explained if a shower is less than 15 minutes, it probably uses less water than a bath.

Alert, maybe overly so, to causing shame, I then told my son, ”taking a shower instead of a bath is something we can do to help, kind of for fun. Some of the biggest users of water in Cambridge are big companies and universities watering their lawns— and I read that soon they will stop that for the winter, anyway.”

My son took a shower and dried off in a soft, hooded towel, pert with panda ears. In the months that followed, we settled into an easy pattern of about five showers followed by one bath. We didn’t bring up the water restrictions again during our evening routines, but I did try to learn what my son remembered from our conversation.

Over breakfast one morning, I prompted him:

“What did we say about the water? I’m trying to remember.”

“That if you are doing a longer …if you’re doing a long shower I would recommend doing a bath? Like that? I would recommend doing a bath, and if you are doing a short shower just keep doing that.”

“Because why?”

“There’s a water limit, there hasn’t been so much rain.”

I pressed on. “How did it feel taking a shower to help?”

“Well, I don’t know. I forgot.”

I learned in the course of writing this article that a low, dry patch of swirling ground, right on my family’s route to my son’s outdoors-based school, is part of the Cambridge Reservoir. I pointed it out to my son one morning, noting how low it was. He responded, as I’ve noticed children tend to do when we grownups reach our most enthusiastic, our voices soaring with the joy of a teachable moment: “oh.”

In the weeks and months following, I’ve been amazed at how much more historical and geographic complexity enters our conversations. Ben Mardell writes in “The Joy and Terror of this Work:”

“Yes there are ways to explain global warming to young children–they can visit a greenhouse and can apply the Goldilocks principle (not too hot or too cold) to life on earth. But I am not sure what preschoolers can do with this information. There is an age when children need to know what is happening to the planet. I don’t think that age is four.”

I’m starting to wonder if it might be five and three-quarters. One warm, 60 degree December day, as we left the eye doctor, the incongruous sight of winter holiday wreaths and fake snow led to a short conversation in which I found myself introducing the idea of climate change. The topic came up again during a bedtime story about polar bears a week or so later. We find ourselves connecting our son’s chatter to broad trends not only in ecology but also hard history. Thoughtful conversations in my son’s kindergarten class about Martin Luther King Jr. led to a few exchanges around the dinner table about state-sponsored racial segregation, and how to respond to unjust laws. Recently, my son asked why another family is “darker than us.” When I later described the conversation to my husband, he ribbed me gently: “you’ve been waiting your whole life for this moment! You got to do the whole speech about melanin!” And I think it is probably about time to start mentioning food waste every now and then.

In March 2025, we took a closer look at a portion of the Cambridge Reservoir. We spoke optimistically– my son said, "when it rains and stuff the water will get higher." But I felt dread as I looked at the exposed rock. As I type now, the patter of spring rain outside is a balm.

Hobbs Brook at Mill St, Lincoln, MA March 12, 2025

Most nights now, my son’s legs turn to jelly when it’s time to go upstairs for bedtime, and just like that, he is much too tired for a shower OR a bath, he claims. It turns out that my husband and I are not willing to restrict our family’s water use as much as our son would like.

Still, I’m glad I invited my son into the conversation about drought and that he gets to learn about issues impacting our community in small, safe ways. What a luxury, an incredible luxury, it is to introduce him to intractable environmental problems this way– a slow, steady drip, my hand on the spigot.

Thanks to Missy Arellano, Ben Mardell, and Amos Blanton for their comments on a previous draft of this essay.