Good Ideas from Good Ideas

This essay describes an experiment with a documentation process called “Good Ideas from Good Ideas” aimed at promoting children's meta-cognition.

Not yet (and the importance of children learning about learning)

If you are familiar with the early childhood project in Reggio Emilia, Italy you may wonder like I do: how can we do that here? The “that” includes the remarkable long term projects, the in depth conversations, and the sophisticated art work the young children in Reggio create.

I began asking this question 25 years ago when I joined the Making Learning Visible (MLV) research team, a collaboration between Reggio and Project Zero (a research organization at the Harvard Graduate School of Education). MLV aimed to explain how the practice of documentation supported individual and group learning in the Reggio schools.

When I shared examples of the children’s endeavors from Reggio with American educators they were always impressed. And they would often say, “Our children can't do that.” I was disappointed by this response, feeling it underestimated the capacities of children. At a loss about how to respond I would joke, “Maybe it is that the kids in Reggio eat that special Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, or have some inborn Italian aesthetic.”

Returning to the classroom in August of 2002, I quickly realized that these American educators weren't wrong. While the children in my class were lively and smart, the in-depth project work that I and other educators admired from Reggio didn’t seem possible. The children didn't have the same ability to focus, engage in dialogue, or learn from and with one another.

My analysis was that their understanding of learning was limited compared to that of the children in Reggio. They hadn't developed the metacognitive understandings –for example, knowing how they could learn from and with peers– that make this sophisticated individual and group work possible.

It is a challenge to create a learning community, and ultimately the shortcomings were in my teaching. Children understanding their learning is just one of the many ingredients that are involved in creating learning communities, and my colleagues and I needed more practice in creating the conditions for learning communities to develop.

And there was no reason to think, even without the cheese, that my children couldn’t develop the capacities to engage in deep project work. So now when I hear educators respond to examples from Reggio with “our children can't” I say, “You're right. They can't–not yet.”

Playing towards meta-cognition

In this essay I describe a playful learning practice that at Newtowne School we call “Good Ideas from Good Ideas.” I share detailed documentation of the practice and explain the concept of recursive prompting (the theory behind the practice). I share possible directions for the practice, and note how the practice is situated within the culture of our school. My conclusion is that the good ideas practice holds promise in promoting children’s meta-cognitive development and thus is supportive in fostering learning communities.

Note, this is a long piece that shares detailed documentation from a week’s worth of activity in the Newtowne Studio. If a deep dive into teaching and learning interests you, pour yourself a beverage of your choice and read on.

Good Ideas from Good Ideas: Spiders edition

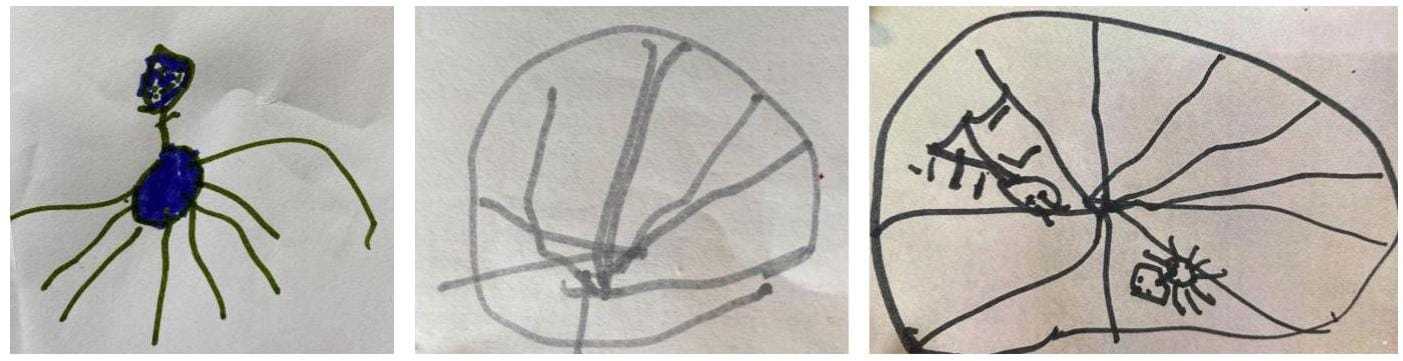

The first whole school inquiry I helped facilitate began in February and focused on spiders. What follows is detailed documentation of a Good Ideas from Good Ideas experiment that was part of this inquiry. Taking place over a week, it involved children from the Green Dragonflies and Blue Otters classrooms (five and four-year olds respectively).

As you read, keep track of where the children’s ideas came from. The documentation makes clear that good ideas have many sources, something important for children to learn about their learning. Note in particular the story of these good ideas from Farryn and Rushaan that I share at the end of the documentation; a story I see as strong evidence that the Good Ideas experiment promotes children’s meta-cognitive understandings.

28 spiders, 4 vehicles, 1 roly-poly, and a piece of cheese

Over the course of the week, 31 Green Dragonflies and Blue Otters, in nine small groups, came to the studio. Each group was told that they would be playing the Good Ideas from Good Ideas Game, focusing on spiders. Each child would be able to create their own spider with a drawing and a story. I explained they could get ideas for their spider from actual spiders, from their imagination, and the ideas of other children.

After each session, I placed the children’s drawing on a poster which was shared with subsequent groups. I would tell each group a story of how the creations connected – Good Ideas from Good Ideas – which grew over the course of the week. I also videotaped children telling about their creations, some of which I shared with subsequent groups.

The final poster allowed me to share a collective story of learning with the children. Before I share that story with you, here is documentation of some key moments from Week One.

Session one: Three imaginary spiders and a black widow

Green Dragonflies Farryn, Sadie, Catherine, and Elijah were the first group to play the game. As they had no peer-created spiders to jumpstart their thinking, I shared photos of Peacock and Orange Orb Spiders from which they could get ideas. I told them they could make multiple drafts, and at the end of our drawing time they could pick one to tell a story about.

Elijah, committed to making a real spider, thumbed through a field guide until he found a Black Widow.

His description began: The Black Widow. If you touch the spider, it could hurt you. So you should never ever go near a Black Widow because it might be venomous. They also have fangs.

Catherine, Farryn, and Sadie decided to make fictional spiders. They each made several drafts, chatting about their creations as they drew. Catherine told her story first:

The Antique Pollen Yellow Spider. Antique Pollen Yellow Spiders can usually be found with Hummingbirds in the forest. I don't know if they have poison but maybe they shoot webs and I think they are all yellow. They might be called the Yellow Spider or the Pollen Spider or the Hummingbird Spider. This is something I made up.

Farryn then shared her story:

This is an imaginary spider ‘cause I like to make them silly. And the black squiggly-squagly is the mustache. And the blue semicircle that you're seeing right now is the mouth. The circle that's about redder and pinker is the lens of the glasses. It has eight eyes but I just decided to make one lens. They can be found anywhere imaginary.

Sadie was the last to share:

This is a kind of spider that not a lot of other people see. It lives only in the forest. It's just pretend; I'm making it up. This spider shoots webs. It can jump really well. It can zoom up to outer space. It likes birthdays and decorations and cakes. It goes out on Halloween sometimes to get candy.

“This is something I made up”, “I’m making it up”, and “This is an imaginary spider” – with these comments, I am struck that all three girls call out the fictional nature of their spiders while incorporating real-world aspects into their creatures (e.g., lives in the forest). In conversations in their classroom, the Green Dragonflies coined the term “niction” to refer to fictional books that have non-fiction elements. Perhaps their conversations about genre increased their sensitivity to the realm of the imaginary. And a creature who can be found “anywhere imaginary” – how wonderful is that?!

“Sadie got a good idea from herself”

During this first session, Catherine made an observation that influenced how I told the Good Idea story to subsequent groups. She noticed that Sadie picked up on an idea in her second draft that she had in her first draft, and called out, “Sadie got a good idea from herself.”

In my attempts to build the culture of a learning community, I often call out children’s ideas. So in explaining the poster to groups at the start of their studio sessions, I included the idea of Sadie getting good ideas from herself. Day Two provided additional material to make this point. Aiden’s first draft was of a spider. His second draft was of a web. His third and final drawing was of a spider in a web.

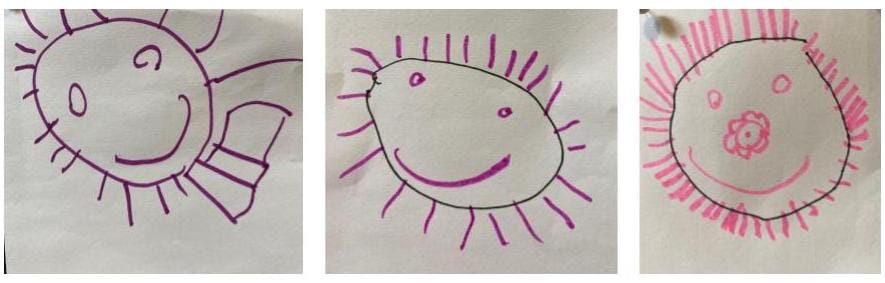

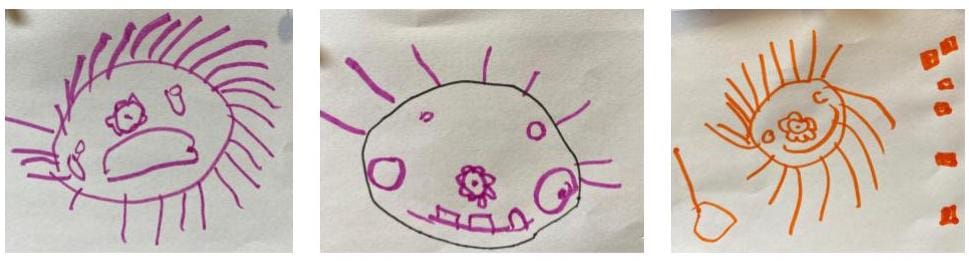

Green Dragonfly Shirley heard how Sadie and Aiden got good ideas from themselves before starting her drawings. She declared “I’m going to make a thousand drafts” and started experimenting with circles to produce different types of spiders.

She used different colors, varied the number of legs, and added a nose in her third draft.

She then varied the emotion of the spiders–sad and then happy.

In her final drawing, the one she chose to tell a story about, she included six spiders.

As the drawing illustrates, Shirely got good ideas from herself.

“What’s a draft?”, “The book is telling me how to draw”, and other sources of good ideas

The invitation to create a spider engaged almost all the children. Sessions alternated between quiet and conversation, lasting 30 minutes or more, an impressive amount of focused attention. The number of eyes spiders have was a recurring topic.

In my invitation to each group, I continued to tell children that they could make multiple drafts. On hearing this, Blue Otter DJ asked, “What’s a draft?” After my explanation that drafts are tries, he proceeded to make seven drawings before settling on his “Octopus Spider that can swim in the water and fly in the sky.”

Using field guides for inspiration was popular with the children.

Looking at a photo of an Orange Orb spider, a Blue Otter told me, “The book is telling me how to draw,” highlighting an awareness of where her idea was coming from.

As the collection of child-created spiders grew, children used the poster like a guidebook, referencing it as they drew.

Peers’ stories were also a source of inspiration. As they drew, Alex, Rushaan, and Hugo chatted about their creations. Ideas from their conversation made it into their stories, as evidenced in their three narratives:

Alex’s story:

So my cutie roly-poly name is Cutester. And Cutester likes eating bugs and he likes eating meat. And he also likes walking around. When a predator bug sees him his body rolls up into a ball. And then the predator can't get in because he's rolled up. He puts out a stinky spray out of his bum. And then the animal thinks he's not tasty. And then he unrolls when the animal is away. And he keeps walking down the forest.

Hugo’s story:

This one's name is Gina [a spider] and this one's name is Roll [a roly-poly]. And this one likes to nibble on flags. They live in the forest. The spider, if a predator comes close to it, it goes down, down, down into the ground. And it looks like dirt, so the predator just walks on it. It's camouflaged.

Rushaan’s story:

The name of my spider is Roll. Because you know, when predators come it rolls itself up into a mat. And the predator thinks it's just some picnic mat. It looks like an old picnic mat and it gets sand put on the top. And the predator thinks it's just a rusty picnic mat that's someone left in the forest. And it walks away from it. When the predator is far away, no predator is close to it, it rolls up back to its size. It keeps walking around the forest.

While Alex, Hugo, and Rushaan’s stories are far from carbon copies, it is clear that they are getting ideas from one another. And they are engaging in a discussion about predators and prey. Despite the fictional elements, they name real strategies – rolling up into a ball, spraying, hiding in the ground, and camouflage – for their creatures to avoid predators.

A story of collective learning

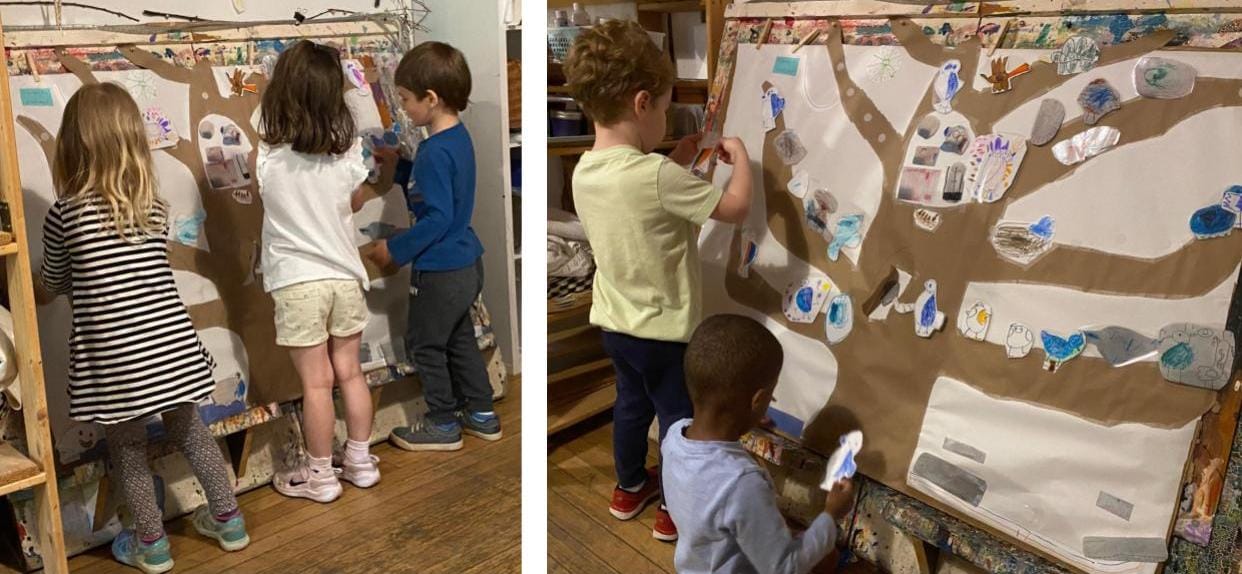

At the end of the week I brought the final poster to the Green Dragonflies’ and then the Blue Otters’ whole class gatherings. With the poster placed in the middle of the group, I asked the children to share their noticings and questions.

Some were keen to point out their contribution to the poster. Others had questions about what certain spiders involved and the stories behind them. I then told a story about how the drawings unfolded, emphasizing ideas arising from previous ideas. As I pointed to individual drawings I recounted:

It starts with the Peacock Spider, a very colorful critter. The Peacock Spider inspired this colorful spider by Benja, that is unnamed and eats cheese. Here is its cheese, drawn by Afomia when she came to the studio the next day. The Peacock and the unnamed spider inspired two other spiders: Anika’s Rainbow Spider and another unnamed spider by Simon. Simon said he wanted his spider to be unnamed, just like Benja’s. The first unnamed spider lives underground, an idea borrowed from Luc’s Tree Spider. Underground is also where Caleb’s Blue Spider and Idris’s Green Spider live. The Blue Spider also flies which is something DJ’s Octopus Spider can do too.

There are a number of spiders that come from children’s imaginations: Farryn’s Silly Spider with a mustache and glasses with just one lens for all eight eyes; Sadie’s spider who trick-or-treats and Catherine’s Antique Pollen Yellow Spider.

I continued the story, pointing out spiders inspired by guide books, spiders living in houses and spiders living in rainforests, and then shared:

Aiden’s drawing has a spider in a web which inspired this very colorful web by Blue Otter Sadie. These spiders, living in webs, are families. Asher drew this one and Kai this one. Avery made a spider family too.

These four vehicles that Henry drew are nervous about spiders but have a safe space to go.

Alex, Hugo, and Rushaan gave each other ideas when they came to the studio. Alex drew this roly-poly bug whose defense is to roll up into a ball when threatened. Rushaan named his spider Roll that also rolls up like Alex’s bug. And Hugo drew a roly-poly bug and this spider that eats flags.

To conclude the story I shared how Sadie, Aiden, and Shirely got good ideas from their own good ideas.

“It started out with the Peacock Spider”: Children tell the story

The next Tuesday I brought the poster to the Green Dragonfly classroom. Since their teacher Vaidehi was absent when I shared the Good Ideas poster the previous Friday, I asked Farryn and Rushaan to explain to her the connections between the individual creations. Four days after hearing my story, they began:

Rushaan: It started out with the Peacock Spider.

Farryn: And this is mine.

Rushaan: And this one is mine. It's a pretend one.

Farryn: And Mateo’s.

Rushaan: And the next one was this [pointing to Benja’s] who ate cheese. So Afomia made cheese.

Farryn: Shirley made that one. And she experimented with different ways to make noses. This is

Asher’s and it's a family of spiders. Sadie made a pretend spider that only comes out at Halloween.

Rushaan: And I made a spider that only comes out in the night. When no people are outside.

Farryn: And it sneaks into people's houses, right?

Rushaan: Yes. The spider leaps out of sharks’s bodies and bursts out. So that they could eat sharks. And whales eat that spider. And you know that Aiden made a web with spiders on it.

He made two drafts before. And then he made two spiders on the web.

Farryn and Rushaan in unison: Henry made cars.

Rushaan: That were afraid of spiders.

Farryn: And this truck is afraid of spiders.

It is clear from their telling that Farryn and Rushaan have, despite not having eaten the Reggio cheese, a growing understanding of how they and their peers can learn from and with each other.

Their story is a proof of concept; that the Good Ideas game can promote children’s meta-cognition (their understanding of learning).

And the desire to build on their peers' good ideas continued. After the explanation was finished, a half-dozen children expressed interest in making additional spider drawings. As they drew, the children commented on their drawings – comments that make clear children were building onideas of their friends:

Rushaan: I’m making a car that’s afraid of spiders.

Faye: I’m making one with a mustache.

Avery: Mine is a family of spiders–three different ones.

Farryn thumbed through a guide book, and finding a scorpion, decided to draw it. Dissatisfied with her first drawing, she asked, “Can I do another draft?” The second draft completed, she explained, “It comes out on Halloweeen like Sadie’s. Actually, not Halloween but October 20th. Maybe it does come out on Halloween to get candy.”

The theory: Recursive Prompting

I find it helpful to know the theory behind Good Ideas from Good Ideas and also find the theory pretty interesting. Here is my take on Recursive Prompting, the concept on which Good Ideas is based on.

Developed by my friend Amos Blanton, Recursive Prompting is a documentation practice that quickly makes ideas visible so they can be shared and built upon by others. It also tells the story of how ideas move through a group. Tangible artifacts (e.g., drawings; photographs of 3D models) are placed on a poster, curated to indicate how ideas were inspired by previous ideas.

The idea builds off of the biological concept of the Adjacent Possible. The Adjacent Possible explains evolutionary change as a series of small steps, each step opening up new possible evolutionary directions. An example is the evolution of the swim bladder and its implications. Developed millions of years ago from the primitive lungs of a lungfish, by allowing fish to stay at specific depths in the ocean without expending energy, the swim bladder created a new ecological niche that thousands of new species soon occupied.

The Adjacent Possible can also be used as a lens to understand collective creativity. Here, new ideas open up the possibilities for other new ideas. For example, the idea of taping pieces of paper up on a wall made possible the idea of Post-its. Post-its opened up possibilities for Jam Board and Miro (electronic note taking system) as well as works of art such as Joseph Grigely’s In What Way Wham?

As Steven Johnson explains in Where do Good Ideas Come From:

What the Adjacent Possible tells us is that at any moment the world is capable of extraordinary change, but only certain changes can happen. The strange and beautiful truth about the adjacent possible is that its boundaries grow as you explore those boundaries. Each new combination ushers new combinations into the adjacent possible. Think of it as a house that magically expands with each door you open. You begin in a room with four doors, each leading to a new room that you haven't visited yet. Those four rooms are the adjacent possible. But once you open one of those doors and stroll into that room, three new doors appear, each leading to a brand-new room that you couldn’t have reached from your original starting point.

Amos explains that recursive prompting opens up new Adjacent Possibles by “feeding forward ideas from past learners so that future learners can build on them.” By making ideas available, it also broadens the range of individuals that can be involved in a project; participants do not have to be in the same place at the same time to be in dialogue with each other. Recursive Prompting promotes children’s meta-cognition by making visible how ideas evolve and connect.

“I got a good idea from…”: Becoming part of the culture

Over the next months, the notion that one’s thinking could be inspired by someone else’s ideas became increasingly more prominent in the school culture. I visited the Green Dragonflies for lunch a couple of weeks after playing the Good Ideas game in the studio. Sitting next to Catherine, I asked how she got the idea to make a drawing of a spider web that was displayed in the room. Her response:

Catherine: I got a good idea from a good idea.

Ben: How did that happen?

Catherine: I was at the drawing table and some kids were drawing homes, so I got the idea to make a spider home.

And a full two months later, Rushaan spontaneously said as he was working with the Playing with the Sun kit, “I got a good idea from Mateo to draw on the mushroom. And Henry got a good idea from me to put something inside the mushroom.”

These were not isolated instances. The Green Dragonfly teachers reported hearing children using the Good Idea language as well. The children hadn’t needed to eat the Parmigiano Reggiano cheese to learn they could learn from and with one another.

Good ideas (and puzzles) about Good Ideas

Whether one calls it Recursive Prompting or Good Ideas from Good Ideas, my experience has convinced me that there is something to Amos’s documentation practice. Next year we will continue playing the game. In future iterations, I wonder about:

Children providing input into the display, helping to tell the Good Idea story. In the initial iterations, I organized the Good Idea poster. What if I asked children to consider where their ideas came from and where they thought their drawing should go? While this might be difficult, the children’s perspective on their ideas would be valuable, and considering the question would exercise their meta-cognative muscles.

Creating opportunities for children to play with the artifacts they and their friends make. Children learn through play. What if, along with seeing and hearing the story of the Antique Pollen Yellow Spider, children could hold it, move it around, and play with it? I experimented with this idea in the spring with another iteration of the Good Ideas game. I asked groups of Green Dragonflies and Blue Otters to draw Blue Jays–then the Critter of the Month. I laminated and put velcro on the back of their creations, so they could be moved around the poster which had a cut out tree for the birds to land on.

Children from all the classrooms enjoyed playing with the Jays, and their play led to some interesting debates about whether birds should be allowed on trains (pro–unfair to exclude them; con–unsafe if they are flying around the cars). At the same time, having the birds be able to alight on different parts of the tree made telling a story about their connections difficult.

Teachers getting Good Ideas from other teachers’ Good Ideas. A hypothesis: teachers getting good ideas from each other increases their sensitivity to children getting good ideas from each other. At Newtowne, the faculty often get good ideas from each other. And at the end of the year we did so in a formal way. As part of our final reflections each teaching team presented a practice they had tried during the year that they felt had gone well. Then other faculty members shared thoughts of how the practice might influence their teaching; what Good Ideas might come from this Good Idea. All four sessions led to lively sharing and appreciation of colleagues' work.

Good people from good people

It is a Newtowne tradition to end the school year with a slide show that includes photos of all the children and faculty (and many family members). Children, families and teachers gather to enjoy memories of the preceding 10 months. This year, Caitlin Malloy, the school's director, introduced the slide show by noting:

This year at Newtowne we've been talking a lot about how good ideas come from other good ideas. If we take a step back from this, I would say that here at Newtowne, good people come from good people. That – as a school community that values care – we are all helping each other be the best people that we can be.

Caitlin’s comments highlight that the iterations of Good Ideas from Good Ideas games were successful because they took place in a supportive culture. The structures, traditions, relationships, and values of Newtowne help children, teachers, and families be our best selves; people who care about each other, are happy to share, and are excited about learning with and from one another. Now that is a good idea.

This essay was greatly improved by feedback from Amos Blanton, Liz Merrill and Caitlin Malloy. My thanks also to the children in the Green Dragonfly and Blue Otter classrooms for taking part in this endeavor.