Playing with the Sun at Newtowne School

This essay shares documentation from initial explorations at Newtowne School with the Playing with the Sun construction kit, providing an idea of how four and five-year-olds can explore the materials and begin to understand solar power.

“Actually, I need to be in the sunlight”

Halfway through an hour-long tinkering activity with the Playing with the Sun kit, Catherine and Aiden begin spinning. In the shade Catherine realizes, like the gadget she is pretending to be, “Actually, I need to be in the sunlight.” Aiden responds, “Me too.” Then, finding himself in my shadow, he pauses, just as the gadget’s motor does when the sun stops shining on the solar panel powering it.

Meanwhile, Mateo is collecting clover he intends to put into the hub attached to the motor. Faye is using markers to decorate the back of a solar panel, adding a truck to the heart and butterfly she has drawn, “so boys will like it too.” Sadie is finishing writing her name on paper she plans to affix to the wheel hub to see what it looks like when it spins around.

At the conclusion of the session, I ask these five-year-olds what they have learned:

Catherine: When my mushroom [which she decorated with markers and placed in the cylinder] spins around, it makes a beautiful and colorful pattern.

Aiden: The sun is the battery.

Sadie exclaims, “I want to do this again someday,” setting off a chorus of, “me too.” Playing with the Sun is a hit with the children at Newtowne School.

A disagreement among friends

My friend Amos Blanton and I had a disagreement. The lead designer of the Playing with the Sun kit and activities (https://www.playingwiththesun.org/), Amos felt that the tinkerable toy he created with help from friends was best suited for elementary age children. He believed that conceptually and fine motor-wise, the materials were too challenging for kindergarten and preschool aged children.

In the contexts that Amos works, libraries and festivals, where children generally encounter the kit only once, he might be right. But I thought that the repeated experiences possible in a school could help young children overcome these barriers.

This past spring, thanks to Amos and Wellesley College physicist and master tinkerer Robbie Berg, the first Playing with the Sun kit made outside of Denmark was delivered to Newtowne School. I facilitated two phases of encounters with the kit. First, I encouraged the children to “mess about” with the materials, getting to know them and explore what the motor might spin. Then I invited the children to create “spinning sculptures” and get other “good ideas” from their peers. These experiences have convinced Amos that young children can productively play with the kit.

In this essay, I provide documentation of these two phases of exploration. Reflecting on this documentation, I hypothesize how my students can continue to learn from the kit during the next school year and wonder about how Playing with the Sun can support my intention to foster children’s solidarity with nature.

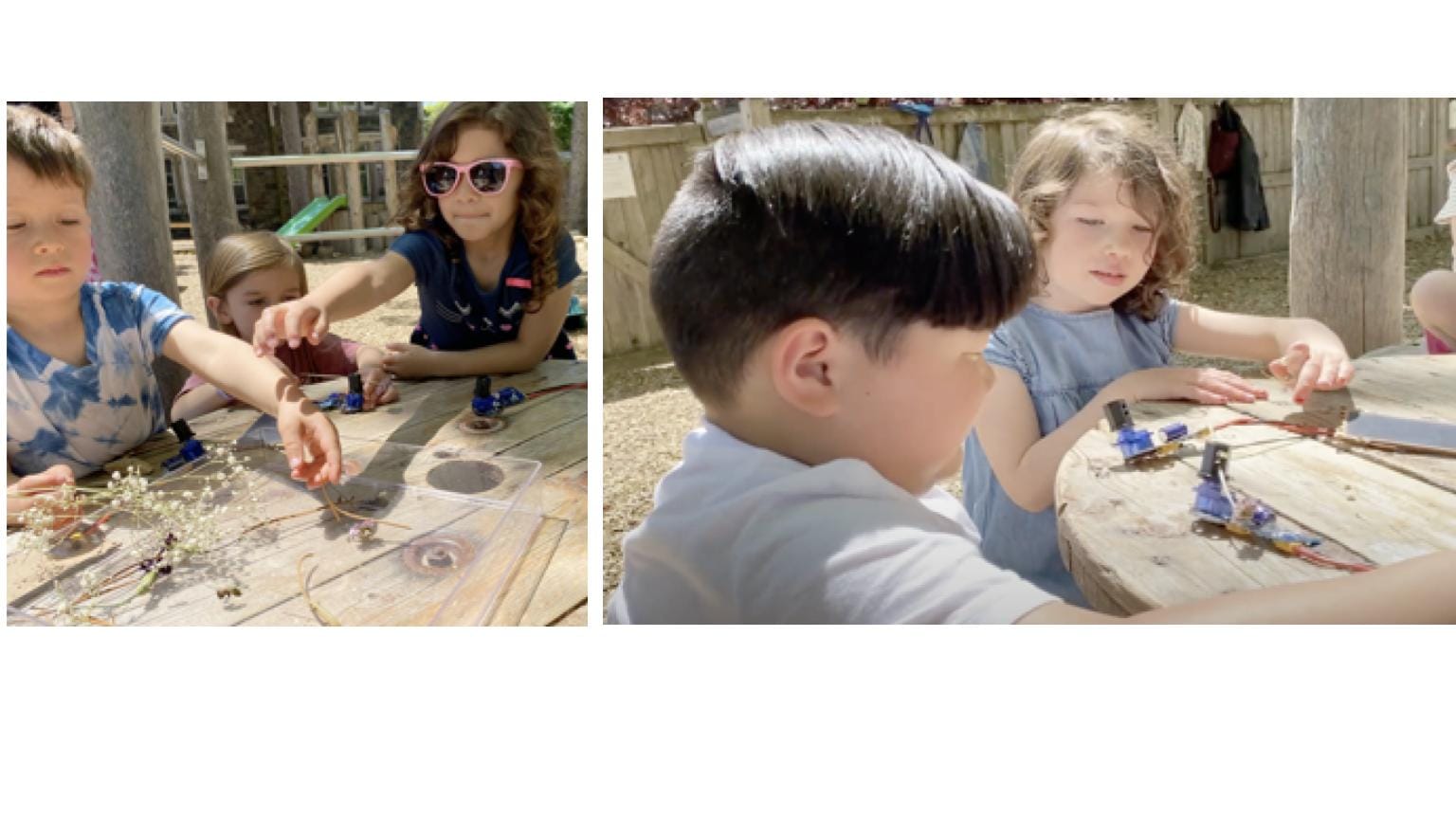

Messing about: getting to know “the gadget”

David Hawkins argued that a good first step in children’s explorations of scientific materials and concepts is “messing about”; letting children play, make discoveries, and find their own questions. To help the four- and five-year-old children in the Green Dragonfly and Blue Otter classrooms become familiar with the Playing with the Sun kit, during four Tuesday playground sessions I connected solar panels to motors that spun an attached cylinder, and invited the children to “see what you can find out about these gadgets.” Though they had the option to dig in the sand, build with wooden planks, go down (and up) a slide, and otherwise play, the opportunity to explore with the kits was engaging to many, some staying at the table with the materials for 30 minutes or more to explore.

On seeing the materials for the first time the children immediately asked questions:

Farryn: What does it do?

Caleb: What is it for?

Elijah: What’s a gadget?

Farryn: Is it 3D printed?

Josh: Where did you get this?

Sadie: Who made it?

Checking out the gadgets, and seeing the motor spin, they remarked:

Farryn: That’s cool.

Elijah: That’s amazing

Afomia: It's going faster!

Kai: Look how fast mine is going.

In messing about, they discovered:

Avery: I stopped it [by putting their hand on the panel].

Alex: I stopped it in a different way [turning the panel over].

Avery: When you undo it [unplug the cord] it stops. And if it's a little undone it still goes.

They also speculated:

Alex: It's electricity. It needs a solar panel. And that’s how it makes electricity. The electricity goes from here to here to here and then to here and it turns the knob.

Ben: What do you mean by electricity?

Alex: It turns on our light. That’s also powered by electricity.

At the start of the second session I asked the children to recall their discoveries from the previous week (e.g., covering the panel stops the spinning) and name the components of the gadget. Their suggestions: solar panel; wires; and spinny or spinner (for the motor).

During this second messing about session those who had sorted out how the gadget worked gave advice to those still figuring it out:

Linnea: Why isn’t it going fast?

Elijah: You just have to wait. Be patient.

Avery: Because you're touching it [the solar panel].

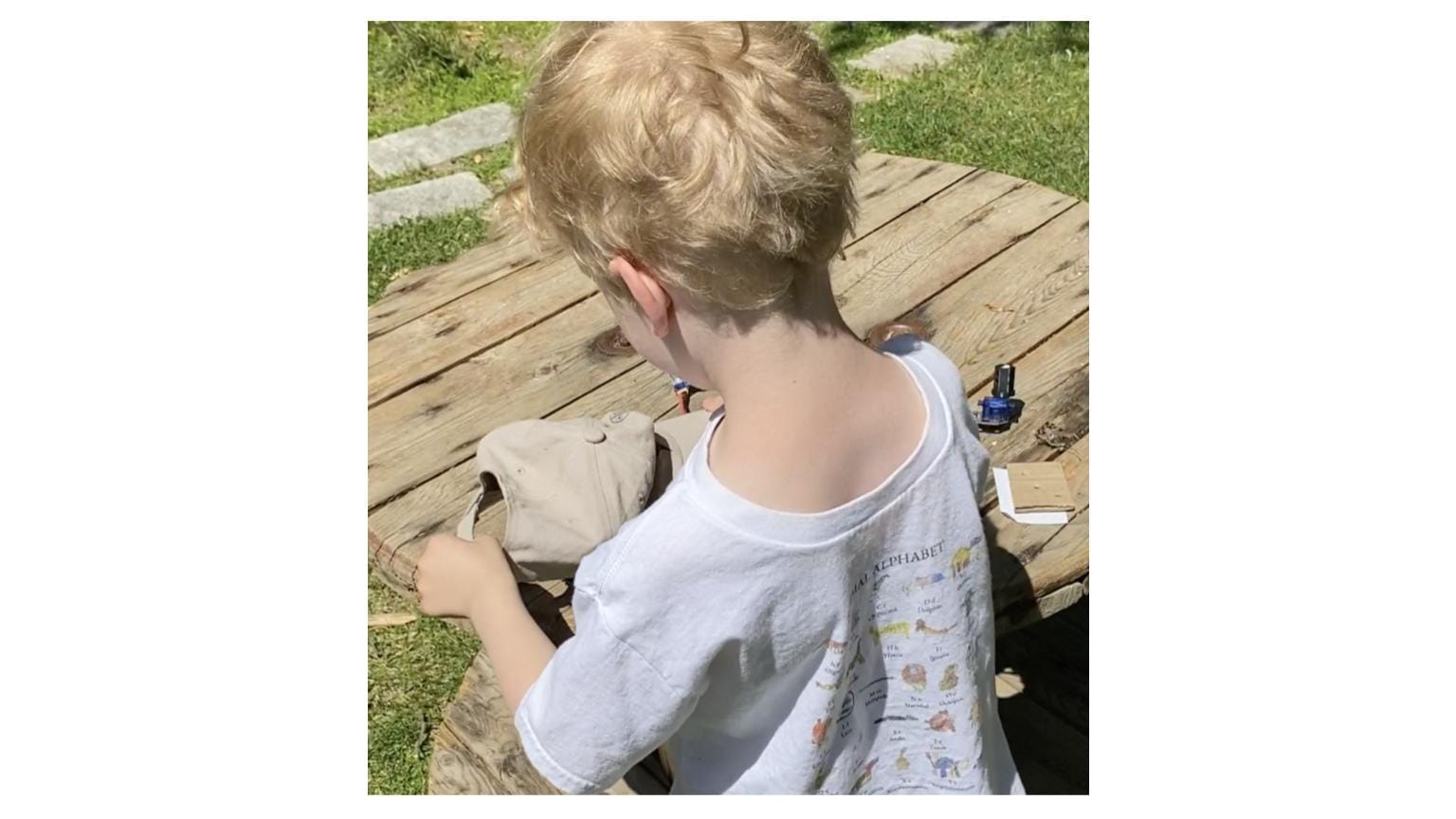

Near the end of the session, Sadie brought a long-handled shovel over to the table. She twisted her body back and forth to “spin” like the solar-powered gadgets —an intelligent strategy to help make sense of the gadgets, one that Catherine and Aiden would also employ.

Reviewing the notes, it was clear that the spinning cylinder was what was most intriguing to the children about the gadgets. So for the next two Tuesdays, I brought out natural materials (flowers, pine needles, sticks) that could be put into the cylinders and spun around. Children used the discoveries from the previous sessions (e.g., turning the panel over stops the motor, making it easier to put materials into the cylinder), and there was focused explorations and messing about.

In the midst of these explorations, Mateo put a flower with its stem bent at a 45 degree angle into a cylinder. As the flower rotated, Robbie Berg, who was visiting that afternoon, commented, “It looks like it is floating there.” Indeed, the flower was like a ballerina pirouetting; the effect was magical. Mateo responded happily, “it's like a statue.”

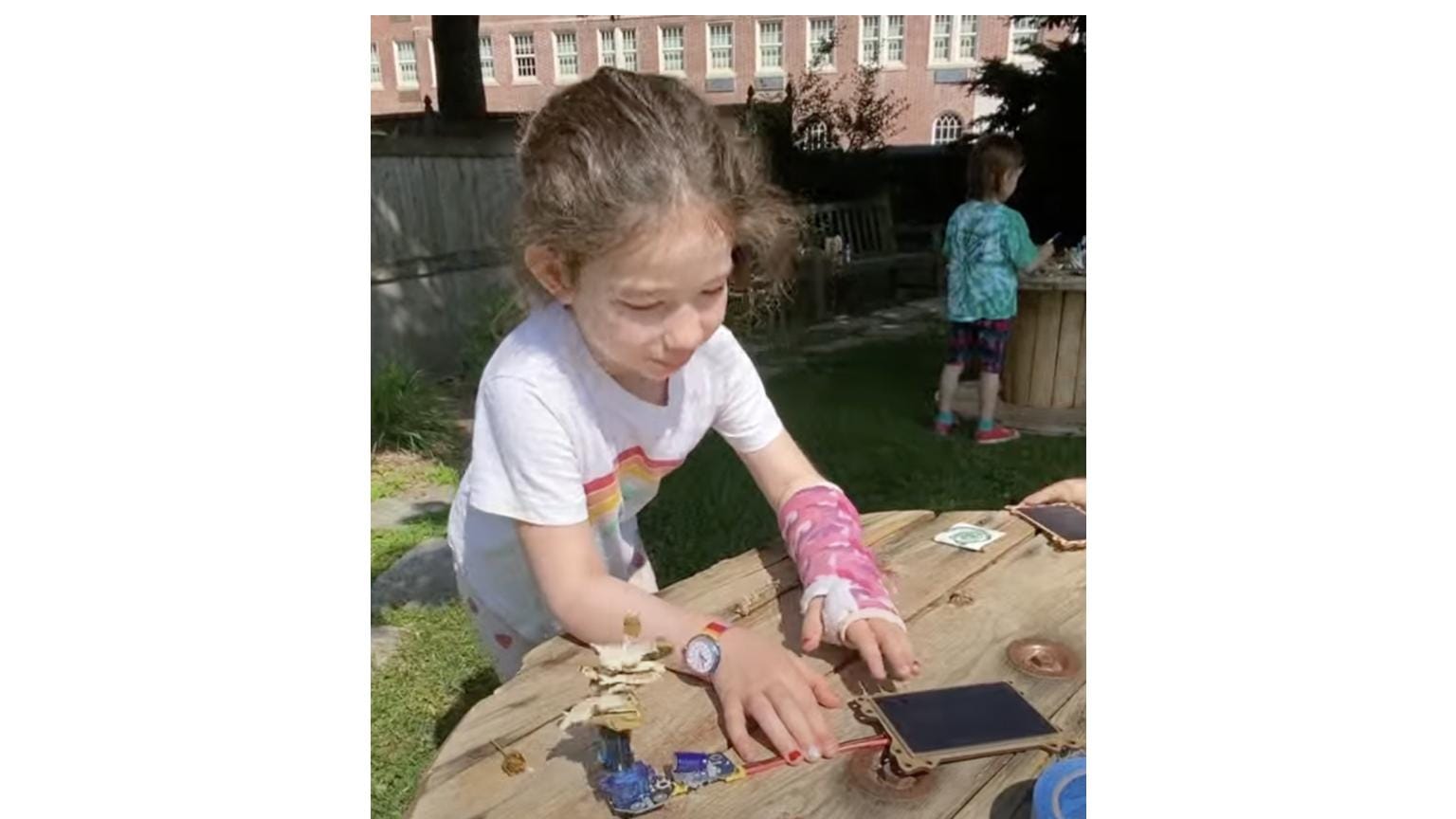

Mateo with his statue

The idea of spinning statues was born.

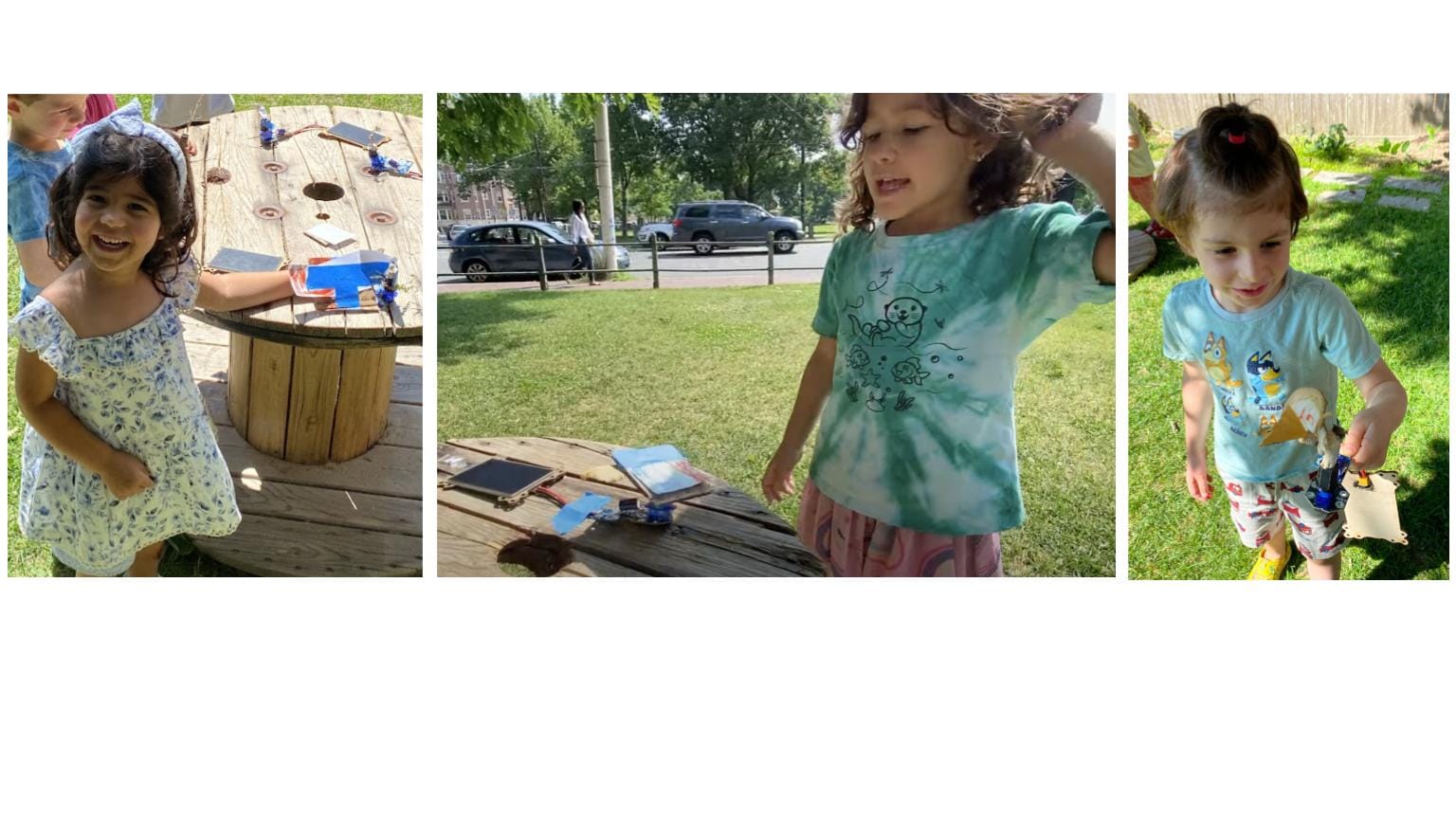

Spinning statues and other good ideas from good ideas

June brought the last full week of school with six one-hour long studio sessions with children from the Green Dragonfly and Blue Otter classrooms, coming in groups of five. With fewer children and a space separate from their everyday classroom, this was a perfect opportunity for children to delve further into Playing with the Sun. At the same time, the element of choice from the playground sessions would be absent, so it was important to craft an engaging invitation to start.

Loris Malaguzzi, founder of the Reggio Approach, used the metaphor of a ping pong rally to describe the back and forth between children and teachers in project based pedagogy. We “serve” children an idea, and they send us something back to us across the net. A prolonged, interesting, and joyful rally is the goal. With the idea of a spinning statue, Mateo had sent a great volley to return, providing the engaging invitation I was after.

I began each session by asking children to recall what they knew about the gadget (a month in, most recalled how the solar panel provided energy to the spinner). I then shared the video of Mateo and his statue, inviting the children to create their own “spinning statues” Sticks, flowers, dried oyster mushrooms we had grown in the studio, cardboard, scissors, makers, and tape were provided.

What followed were focused,

joyful explorations,

with children using past discoveries (e.g., covering the solar panels to stop the motor, making it easier to put materials into the cylinder),

and making new ones (e.g., that a hat can serve the same purpose as a hand to stop the motor spinning),

as they added materials to the gadgets to create spinning statues, “asteroid detectors”, and other creations.

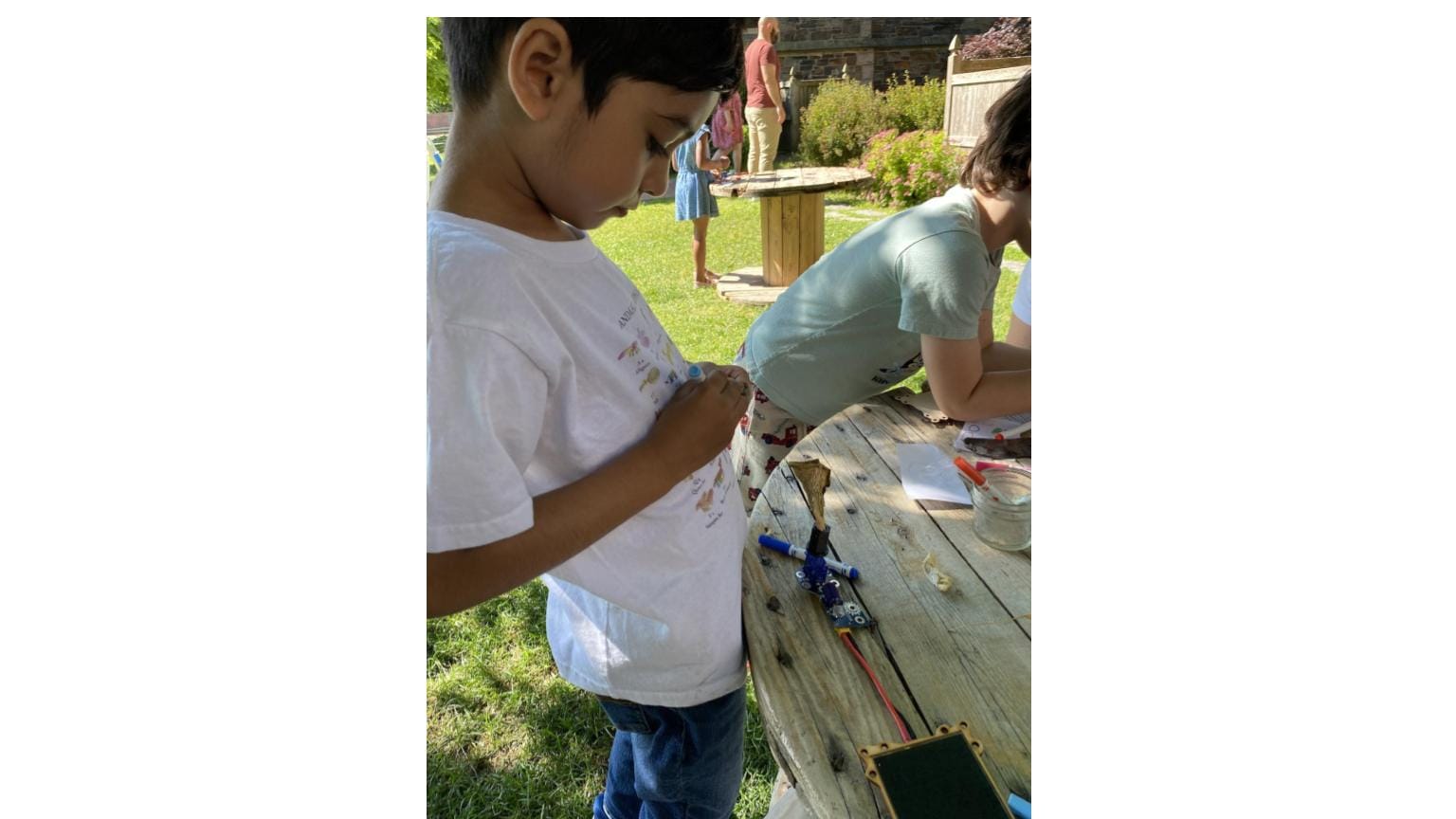

During the first Green Dragonfly session, Rushaan provided me another “volley” to return.

As he added materials to his gadget he told me, “I got a good idea from Mateo to draw on the mushroom. And Henry got a good idea from me to put something inside the mushroom.”

Rushaan’s comment that “I got a good idea from…” harkened back to conversations in the studio during the winter, where I highlighted how the children could learn from each other. While I hadn't used the good ideas language with Rushaan’s group in this PwtS session, I did with subsequent groups. Along with describing Mateo’s sculpture as a good idea one could build upon, I shared other “good ideas” devised by previous groups which could inspire other good ideas.

Children in subsequent groups borrowed, built on, and ignored the good ideas I shared. They were also inspired by ideas developed by children in their own group. The following two vignettes illustrate children learning from and with one another, getting good ideas about process as well as product.

"Back to construction"

During his session, four-year-old Caleb was constantly trying ideas out, seeing how they worked, and making modifications based on what he observed. Working in the shade so the motor wouldn't rotate, he would place various materials in the cylinder, and then take his gadget out to the sun for testing. As he worked he would mutter:

"This might not work."

"Let's test it out.”

"Back to construction.”

Anika was also part of this group. While she didn’t interact with Caleb (she was often talking to her friend Viola), she clearly observed his method. When I asked how she made her sculpture, created through much trial and error, she explained, “I kept on doing the same as Caleb.”

“It's called the spinning statue mushroom...and its an asteroid detector ”

Five-year-old Farryn was part of the final Green Dragonfly group to explore the kit. After I shared Rushaan’s idea of placing material inside an oyster mushroom, she immediately started trying to fit one mushroom inside another. She worked determinedly for the entire session, cutting, taping and eventually layering six mushrooms together, finally placing them into a cylinder.

In the same group, Alex and Avery declared that they were constructing “asteroid detectors”. They had complicated narratives explaining how their creations warned about approaching asteroids.

At the end of the session, I asked Farryn to tell me about her creation.

Farryn: I used a dead flower to put mushrooms on and then I taped it to the gadget and now it's a spinning statue.

Ben: Does it have a name?

Farryn: It's called the spinning statue mushroom...and it's an asteroid detector.

More good ideas from good ideas.

Keep spinning and puzzles about what's next

During one of the Blue Otter sessions a couple of children from the Purple Fish class–soon to be a Blue Otter–was transfixed by his older schoolmates’ experiments with the Playing with the Sun kit. While most of his classmates dug in the sand or played in the playground's mud kitchen, he stood on a platform by the fence watching. His teacher Sarah relayed his request, “They want to know if he can play with these materials when they are Blue Otters?” The answer, “Of course.”

Building off the spring explorations, I imagine that inquiry into spinning continuing in the new school year. Aiming for an extended ping pong rally, I wonder:

If and how to incorporate the children’s spinning into the inquiry?

Sadie, Catherine and Aiden were far from the only children who spun in response to the gadgets. Partaking in what Seymour Papert called body syntonic reasoning, they were physically exploring what the kits were up to. The children’s continued spinning will likely require little encouragement, and I wonder if this is something to build on? Should I record the spinning and then share the video with the children and discuss? Might I call this “solar powered dancing” and add music to the experience? Or is the fun here that children are in control, and that my interference will diminish their interest in spinning?

Should I propose a collective spinning sculpture?

Democracy involves sharing opinions, listening to other people’s ideas, and working together to create and solve common problems. The challenge of putting gadgets together to create a collective spinning sculpture would provide an opportunity to practice these democratic skills. Children would have to negotiate the placement of their gadgets, and perhaps modify their work to harmonize with other parts of the sculpture. It might not be an easy process, and I think ten gadgets spinning together would look really cool.

How to connect Playing with the Sun with the studio intentions?

Time with the children in the studio is a limited resource. With so many directions the curriculum could take (young children have so many interests), I have articulated two main intentions to guide choices regarding our emergent curriculum:

- Foster solidarity between children and nature

- Support projects that bring the Newtowne community together

While it is easy to foresee long term projects involving Playing with the Sun, what about solidarity with nature?

I have two thoughts. The first involves energy. Like plants, the Playing with the Sun gadgets get their energy directly from the sun. The birds that visit our feeders and the squirrels we see jumping among the trees, along with the children themselves, need energy. Perhaps the kits could be a through line about an awareness of the importance of energy and its sources.

Second, using natural materials with the kits blurs the boundaries between what is human-made and non-human made. Like birds that use string, plastic bags, and even barbed wire to build their nests, the children’s incorporation of mushrooms, pine needles and flowers breaks down the distinction between humans and the rest of nature. Activities that challenge this false dichotomy are important in building children’s solidarity with the natural world.

I am in the process of figuring out how to talk to young children about energy and the connections between people and nature. If you have thoughts about this, or a good idea about what to do next school year with the Playing with the Sun, let me know.