What we talk about grows: The Critter Count

This essay discusses the Newtowne School Critter Count, an effort to increase my community’s attention to the animals we share our city with.

Three critter sightings one day in June

Animal sightings on the Newtowne School playground one day in June included:

Benja finding a bug and bringing it over for me to see. Other children become interested and clammer for a turn to hold the insect.

Elijah pointing up to the sky, exclaiming, “Red-tailed Hawk! Red-tailed Hawk!” Elijah’s shouts draw a crowd of excited children (and adults), including Afomia, who embraces him out of pure exuberance.

Josh telling me with great urgency, “I just saw some Slingy Dags! We need to add them to The Critter Count.”

Many young children are intrigued by insects, and Red-tailed Hawks in flight are majestic. So the first two sightings are not remarkable, though I would argue that our school culture promoted the collective excitement among the children. But who are Slingy Dags, and what is The Critter Count?

In this essay, I discuss The Critter Count – an effort to increase children’s (and adults’) attention to the animals that we share our city with. I explain the origins of the Count, share some documentation of how it unfolded in its first year, and hypothesize about how it might evolve in the next school year. I'll also explain what Slingy Dags are.

"There is no nature in Boston"

A decade ago I helped write the kindergarten curriculum for the Boston Public Schools (the city directly across the river from Cambridge where I live and work). The curriculum’s fourth and final unit was to be about the natural world. Taking the advice of my mentor, science educator Karen Worth, I advocated for a focus on squirrels, Sparrows, spiders, and Sycamore trees – what the children could directly observe and interact with at home or at school. I lost this argument.The director of the Early Childhood Department declared, in no uncertain terms, “There is no nature in Boston.” The children ended up studying animals that they could only see in books or at the zoo.

The statement that there is “no nature in Boston,” or other cities for that matter, isn’t true. Along with people, there is a host of flora and fauna that survives and even thrives in human built environments. However, the director’s misconception isn’t uncommon. Many believe that one has to get out to the countryside, or at least the suburbs, to experience nature. It is important to push back against this misconception. Saying there is no nature in a city means there is nothing to care for; nothing to have a relationship with. At a time when children and adults need to form caring and sustainable relationships with the natural world, statements such as “there is no nature in Boston” are more than incorrect, they are dangerous.

Young children know that there are birds and worms and flowers in the city. They notice and talk about them. They also notice buildings, fire trucks, traffic lights, and people. Families and educators shape and socialize the noticing of young children by responding positively to some observations and ignoring others. The result is that, for some, a belief that there is no nature in cities develops.

"What we talk about grows"

Over the years, I have observed that organizations often have something, apart from their mission, that is cool for members to talk about. In some, it is football and the upcoming big game. In others, it is a reality TV show. At Project Zero, a research organization where I worked before coming to Newtowne, it is art exhibits, especially those in New York City. The result is, by being a member of an organization, one becomes more aware of certain things. During my time at Project Zero, I saw art that I would not have otherwise seen. I am grateful for that.

As author and activist adrienne maree brown argues, “what we talk about grows.” I want the flora and fauna around our school to be the cool thing that children, teachers, and families talk about. I view growing an awareness and attention to the nature of Cambridge as a first step in fostering solidarity with the more than human world.

In this effort, the good news was that I wasn't starting from zero. During my first couple of months at Newtowne, I noted that among the topics talked about were nature sightings in Cambridge: a Paper Wasp nest across the street from the school; really big leaves from a Sycamore tree; and a spider in the Purple Fish classroom. My goal was to have the natural world talked about even more.

Take One: Newsletters

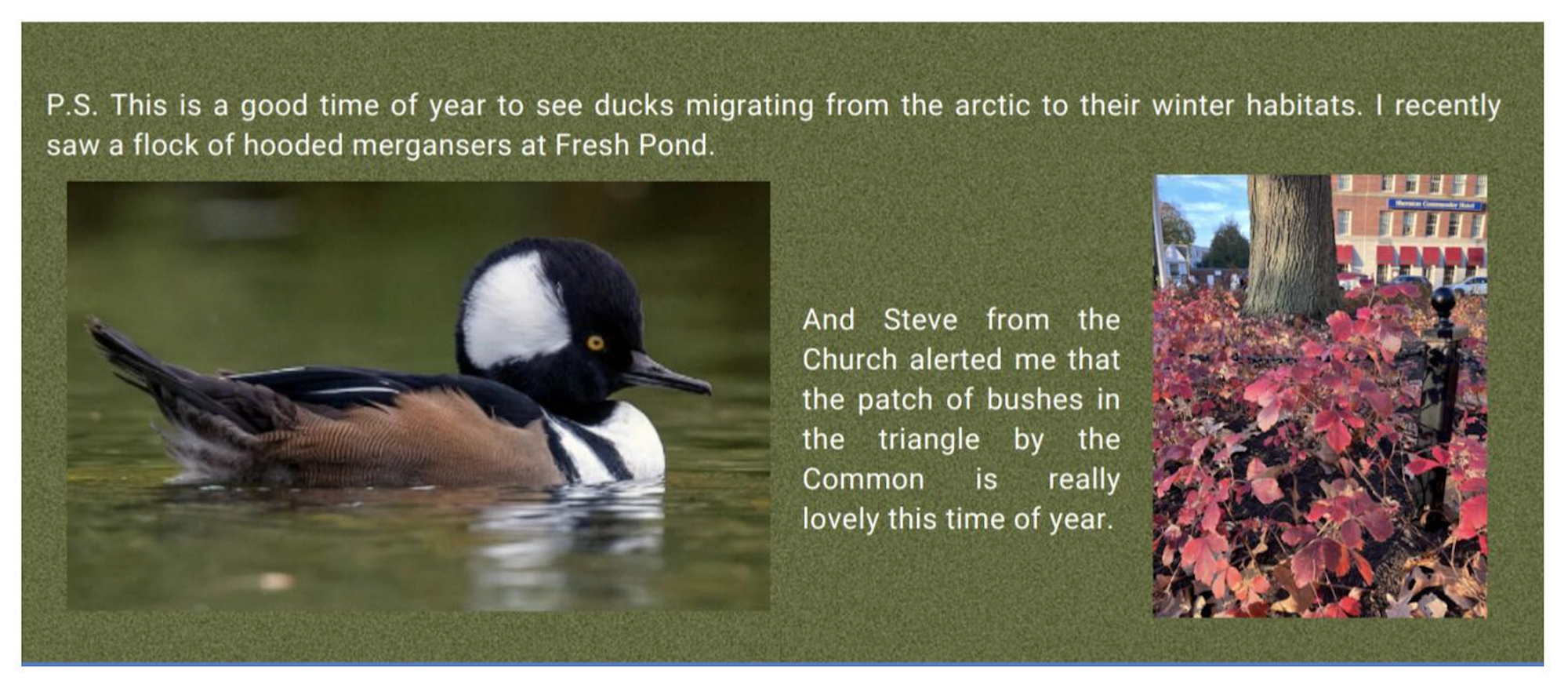

In November, I started putting notes about nature sightings in our school’s bi-weekly family newsletter. I let folks know about the Paper Wasp nest, a sighting of Hooded Mergansers, and when to watch the full moon rise in December (a good month for young children to catch this because it happens well before bedtime).

While I enjoyed thinking of what to include in the newsletters, I wasn’t sure how many parents had the bandwidth to read this part of the newsletter, and wondered about other ways to increase awareness in the Newtowne community of nature in Cambridge. From these wonderings, the Critter Count was born.

The Critter Count launch

January saw the launch of the Newtowne School Critter Count. Children, families, and faculty were invited to share sightings of birds, bugs, and mammals. With the help of parent Sam Blackman, I set up a page on our website to keep track of sightings.

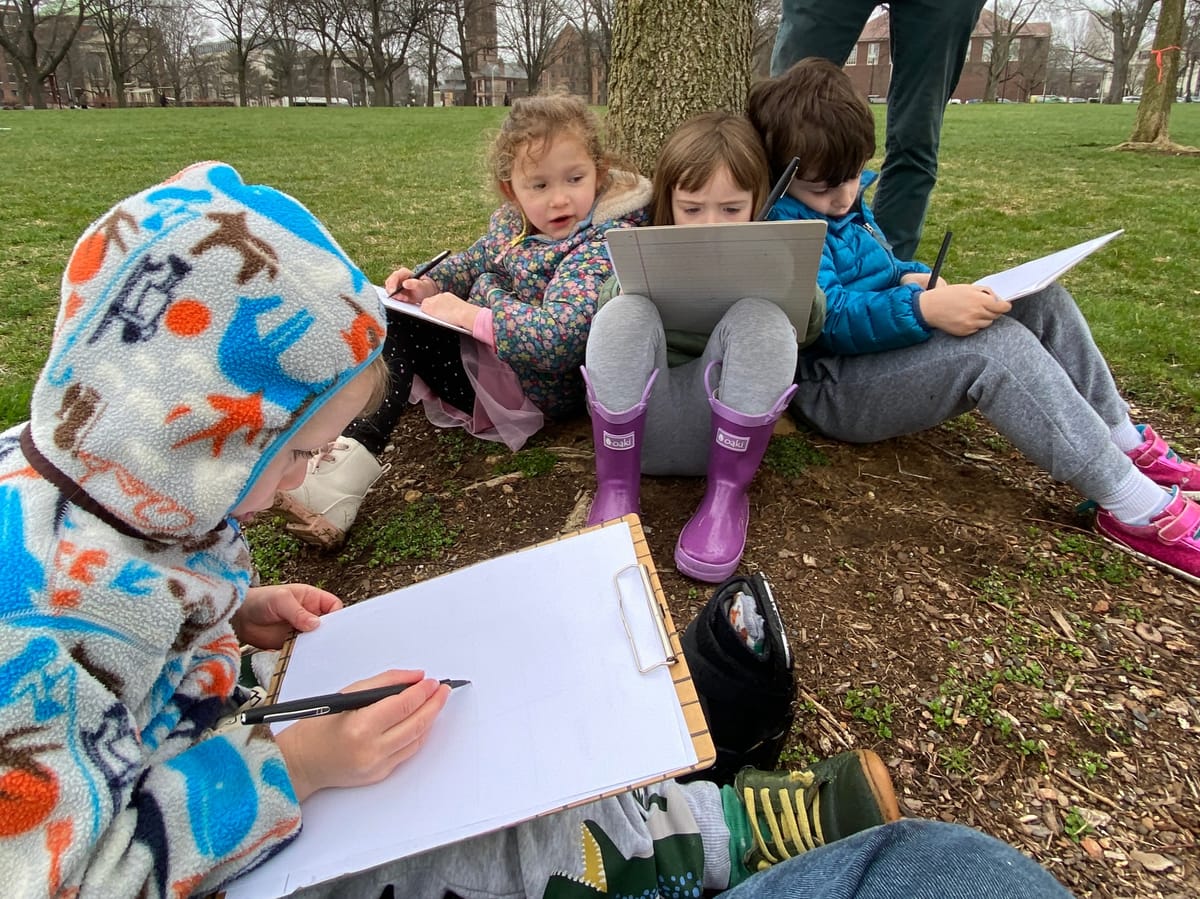

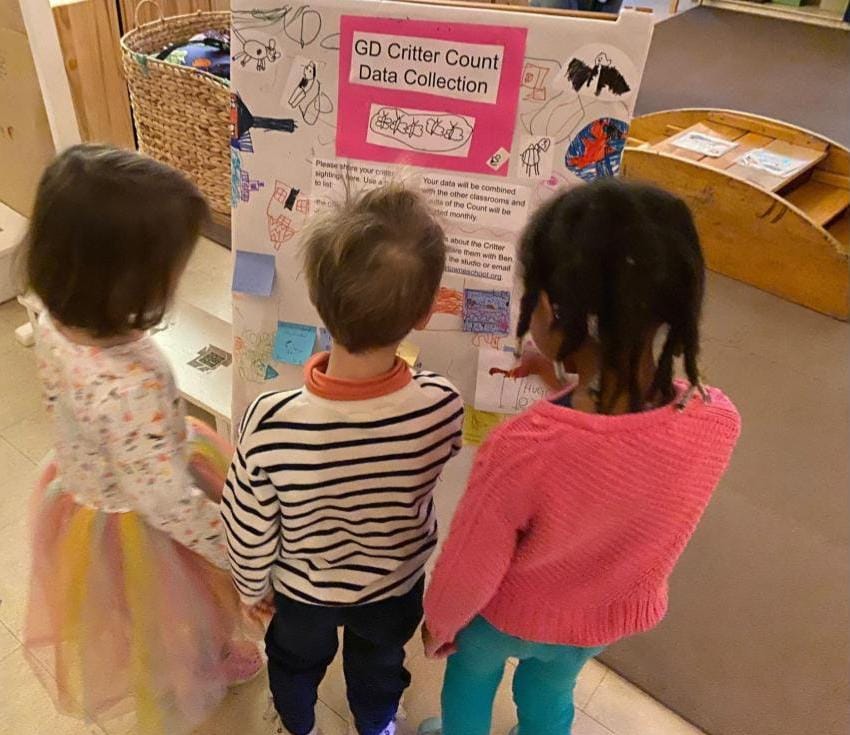

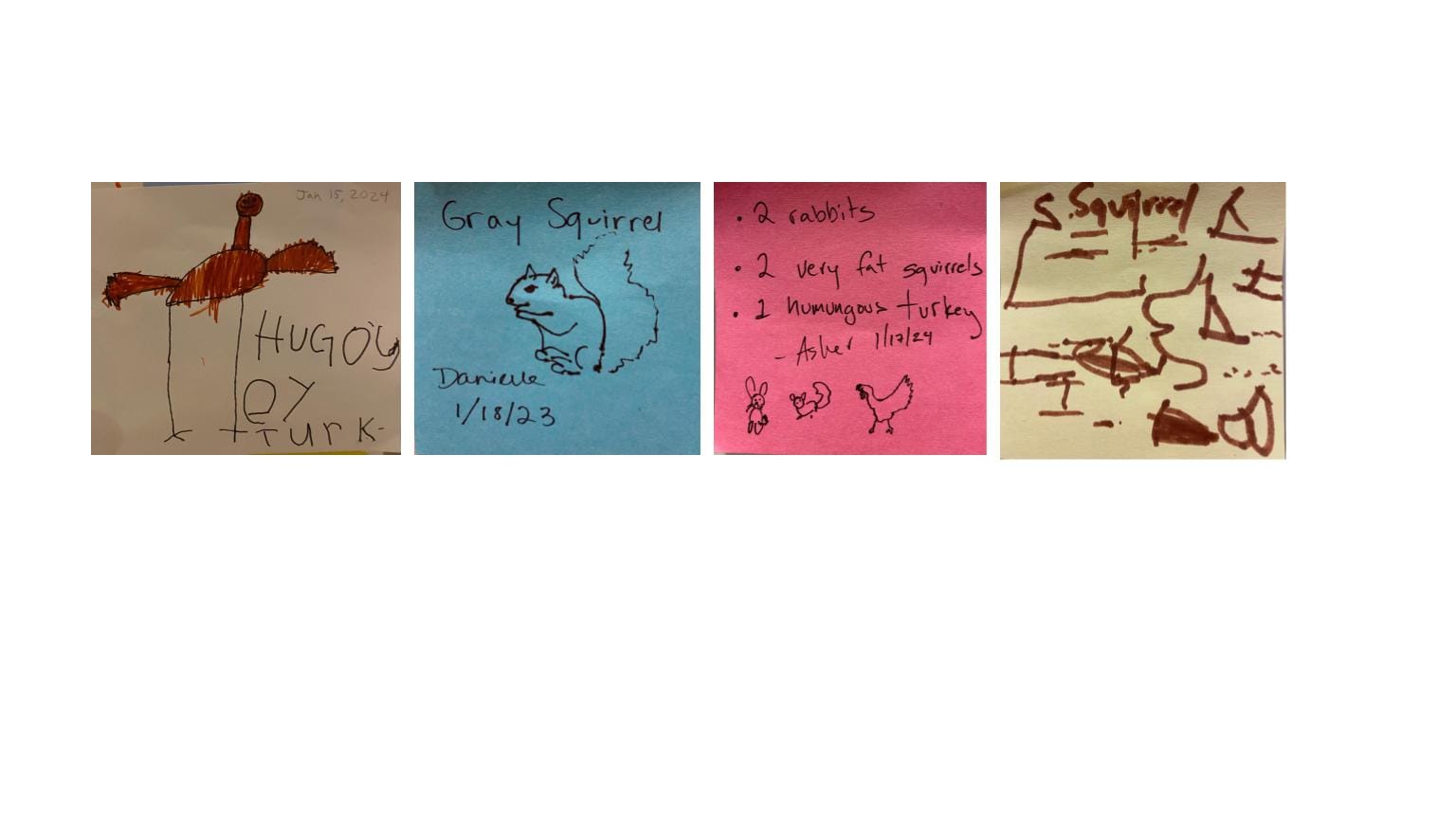

Knowing this was the first census-like activity the children were participating in, I thought of ways to build excitement and understanding about The Count. In their studio time, children in the Green Dragonfly and Blue Otter classrooms helped make data collection boards that were posted around the school.

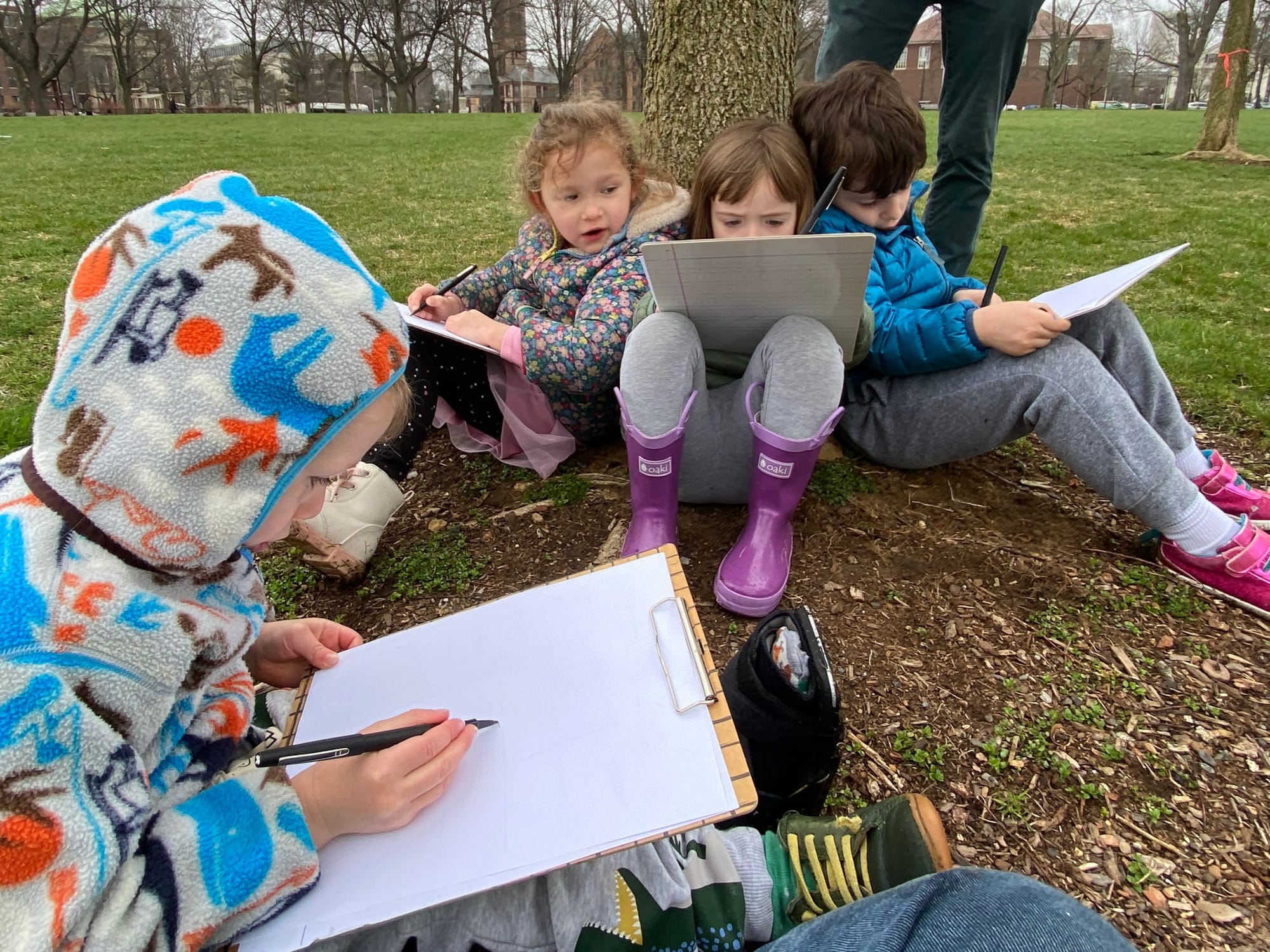

I took groups from all the classrooms to the nearby Cambridge Common to look for critters. Before leaving on the “Critter Count Walks”, I asked children to anticipate who they might see. Predictions included giraffes, lobsters, and dinosaurs. We did see squirrels, dogs, and a flock of Starlings.

I also encouraged the children to keep an eye out for animals while they were inside.

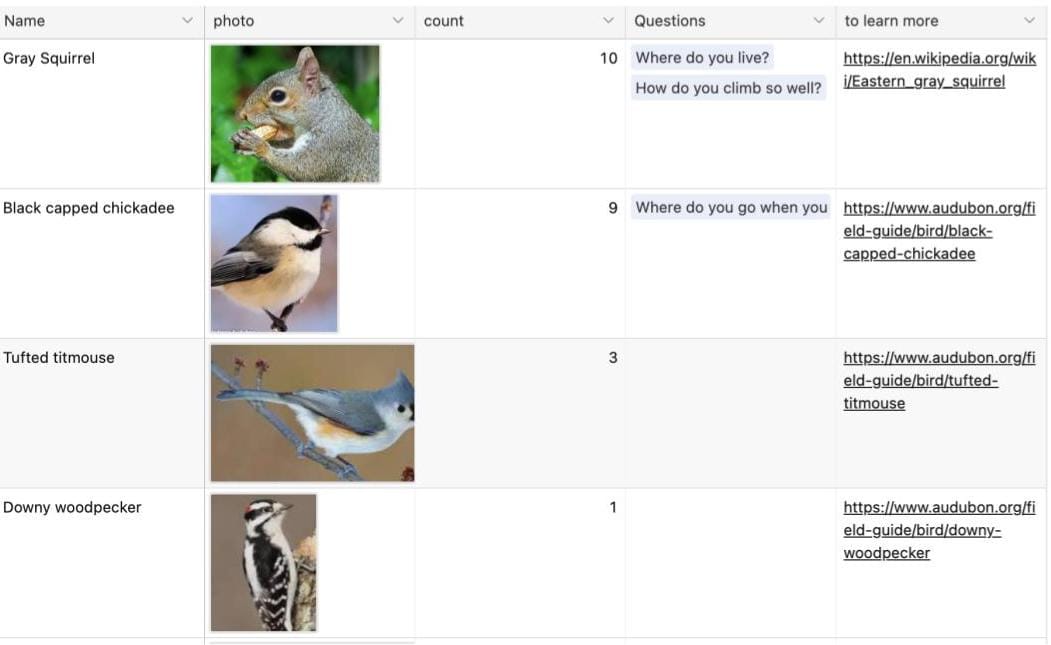

While January is a quiet period for animals in Cambridge, during the first weeks of the Count, 17 different species were recorded.

An ebb and flow of sightings

Over the next five months, there was an ebb and flow of interest and attention to the Count. After an initial flurry of posts by children, families, and faculty, there was a noticeable drop-off in activity on the data collection boards.

To maintain interest in the Count, I posted questions on the data collection board (e.g., “Last week Jenna and Silas saw a Downy Woodpecker, and Phillip saw a Red-tailed Hawk. What will we see this week?”), and sent letters to children who posted on the boards to acknowledge their sightings. I also shared new species sightings in the family newsletter.

A pattern emerged: a handful of parents from each classroom incorporated the Count into their family culture. They made posting on the data collection boards part of their drop off routine. On weekends and vacations they had family critter counts.

Blue Otter Ariel’s family is a prime example. Ariel and her parents would look for animals on their walk to school. Her parents would then help Ariel share sightings on the data collection boards (a great literacy activity).

New to Cambridge, they were genuinely curious about the birds they were seeing and would ask me about them. Ariel’s mom was keen on seeing a Cardinal which she had heard was striking in appearance. And on April 1st, the family posted the most playful sighting of the year:

Critter of the Month

Over time, 31 different species were seen in and around the school. The list served a critical role in another practice created to foster the children’s solidarity with nature: Critter of the Month.

To spur deeper inquiry into nature in Cambridge, starting in February, a class would select an animal for the entire school to learn about. The Critter Count was the pool from which these critters were selected.

So no giraffes, lobsters, or dinosaurs became the Critter of the Month. But spiders, rabbits, Blue Jays, and a specific squirrel were selected.

Keep counting

The Critter Count will continue. I have reset the webpage, and we’ll see how many

different species we find in a new school year.

Based on how the first year unfolded, I realize it is unrealistic to expect a constant focus on the Count. To keep things fresh, I imagine working with my colleagues to highlight the Count one week a month, perhaps in anticipation of the selection of a new Critter of the Month. In addition, I wonder about:

-Expanding the focus of the Count to include plants. Asking where a critter was seen (on a tree, in the grass) might raise awareness of the connections between flora and fauna.

-Making the seasonal component of what critters are seen visible to the children. That we stop seeing certain critters during the colder months might raise questions about where they went.

-Comparing our Count with other schools. If you would like to be pen pals with us regarding what critters you and your kids are seeing, let me know.

Two concluding stories: “Slingy Dags” and “Mourning dove!”

If you don’t know what Slingy Dags are, you are not alone. Here is the story.

During a week in April, I took groups of Green Dragonflies to the Cambridge Common to search for critters. Along with Robins, Starlings, and squirrels, the first group encountered a swarm of insects that would appear and disappear. At the end of the visit, I helped the children write a letter to their classmates about what they had seen and they mentioned these “tiny insects.”

The next group also encountered these insects (perhaps gnats, I’m not sure), and were excited that they had seen them, too. They included these appearing/disappearing critters in their drawings of what they had seen at the Common.

The insects appeared again during the third visit. Isaac declared that they were “Slingy Dags” In a whole group gathering that followed this visit, the Green Dragonflies embraced the name. Children started telling tales of Slingy Dags (e.g., Hugo told of a swarm that formed the letter H before disappearing). Our music teacher Alastair Moock included Slingy Dags in a song that he wrote and sang to all the children called “Newtowne Wonders”, which is how Blue Otter Josh heard the name.

Giving children the opportunity to name the Slingy Dags in this playful way was fun. It was democratic. It fostered the children’s interest in and connections to this tiny critter.

And one more story. June saw other noteworthy critter sightings in the Purple Fish classroom. First thing in the morning, three-year-old Aaraj would make a beeline to the window with the birdfeeder. If there was an avian feeding he would excitedly, and correctly, call out: “Blue Jay!”, “Robin!”, “Cardinal!”, or “ Mourning Dove!”

Aaraj was not alone in his enthusiasm about these visits to the bird feeder. Often Nathan, Iris, Silas, and Phillip would join him along with one of the teachers. Together they would watch the birds alight, grab a seed, fly to a nearby tree to eat it, and often return to the feeder for more food. Smiling, they would talk about their sightings. It seemed they could watch the birds all day.

What I find most noteworthy about these critter sightings is not that three-year-olds were correctly identifying different species, though this is cool. At the start of the year many of these children spoke little or no English, and the strides in language, along with their abilities to classify are impressive. Nor is it most noteworthy the prolonged attention span the children displayed. Though again, at the beginning of the year these “pandemic babies”, most new to group care, generally flitted from one activity to another. In this context, their prolonged attention is an important development, the ability to attend being critical to their future learning.

What I find most noteworthy in these critter sightings are the relationships that developed through the common interest in seeing the birds. The Purple Fish teachers Sam Liptak, Jenna Rounds, and Sarah Milofsky created an emergent curriculum around birds that captured the children’s attention. Through this attention a web of caring connections developed, between humans and other animals and between the humans themselves. In the Purple Fish classroom, birds were something cool to talk about. These conversations allowed children to see one another more deeply, opening up pathways to friendship. What we talk about grows, and when we talk, community can blossom.